Controversial ‘New Deal’ Calendar Restored for 2018

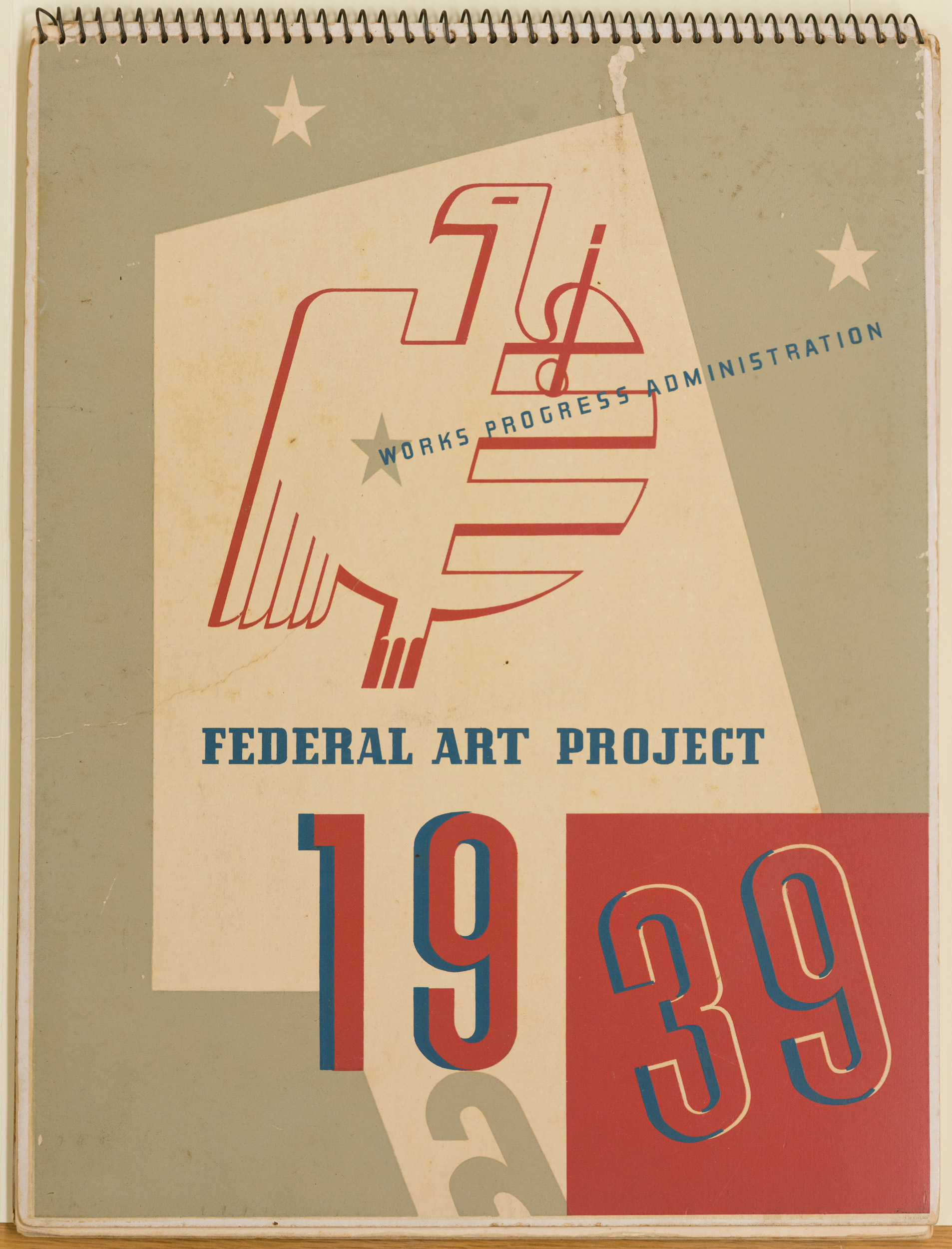

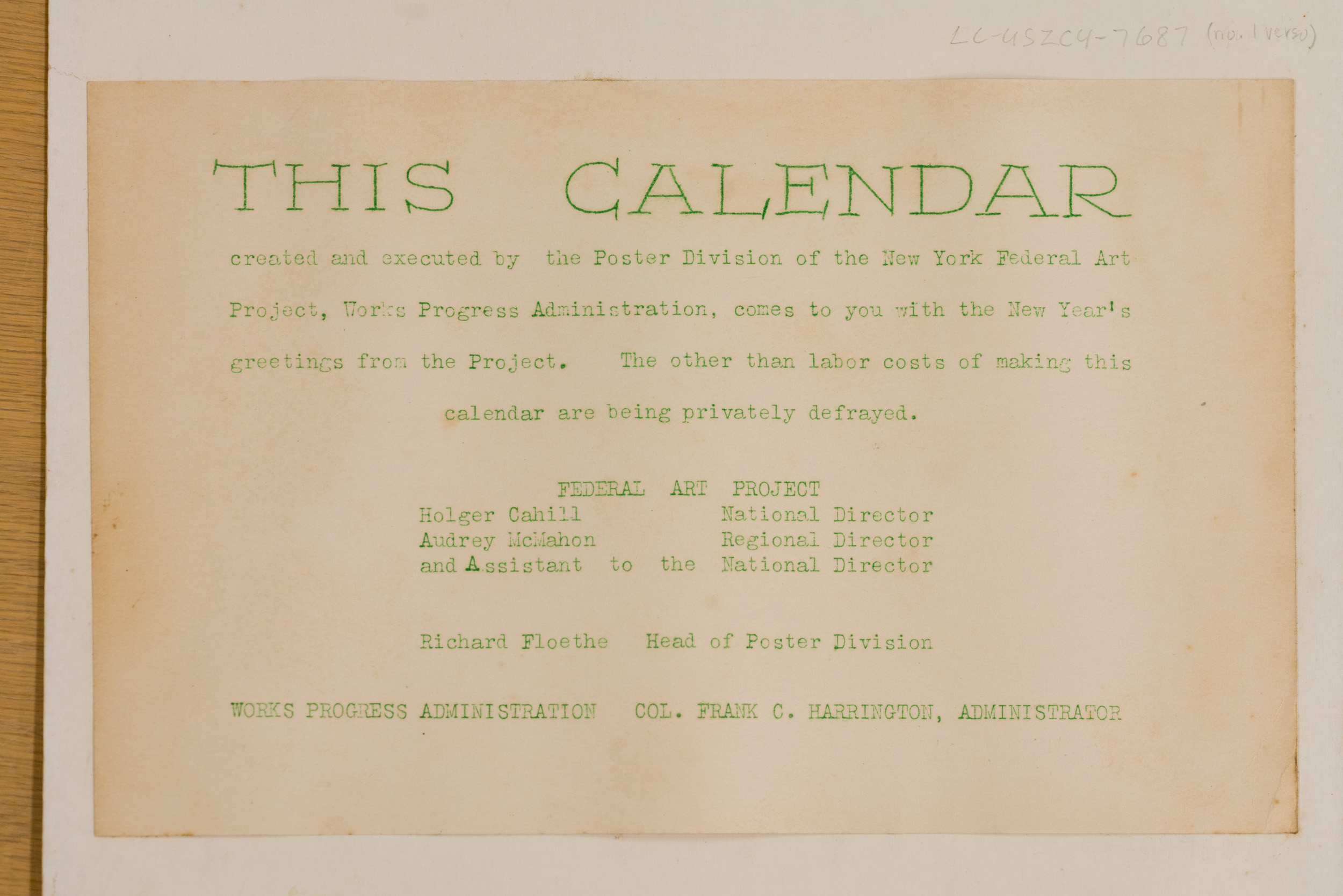

In 1938, the regional director of the Federal Art Project asked the group of artists and printers in the New York City Poster Division to design a calendar as a showpiece to give to members of Congress, but the idea backfired.

“The idea was to make friends and supporters for the Federal Art Project. The result was not what we expected. A congressman rose in the House waving our gift calendar and accused the Art Project of squandering taxpayers’ money. There followed what I would describe as a ‘stink.’ There were threats that heads would be rolling.”

Opening an original calendar

Only a few hundred calendars were likely produced, and most of those probably had a fate similar to that calendar waved on the House floor: discarded as ‘wasteful’ ephemera.

I came across this calendar while researching posters designed by the New York City Poster Division, one of at least 18 poster divisions across the country created by the Federal Art Project. The Library of Congress has one copy of the calendar in its archive, donated by Richard Floethe, the NYC Poster Division’s director. Flipping through it in person, I was inspired by the cohesiveness of the artwork, and the lovely, quirky details in all the hand-drawn letters and numbers.

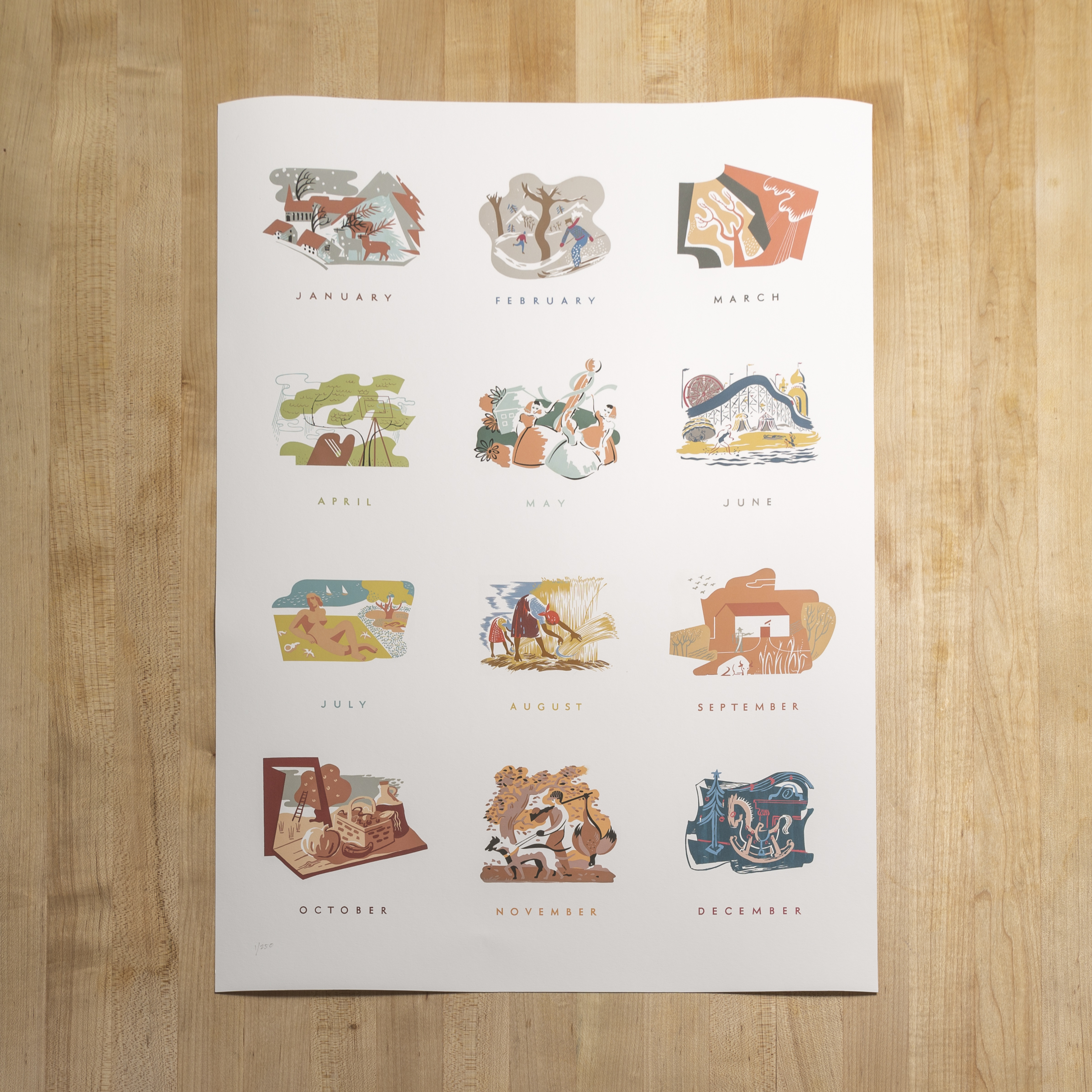

Despite the similar style of each month’s artwork, the illustrations are designed by eight different artists. The calendar shows off the technical skill of the Poster Division’s artists in the then-new medium of serigraphy (fine art silkscreen printing), and their ability to work collaboratively on a unified theme. I’ll write a bit more about the WPA and the NYC Poster Division on the Anchor Editions blog soon.

llustrations and artists

January: Winter scene by Harry Herzog

February: Snow scene by Ben Kaplan

March: Landscape by Richard Halls

April: Rain by Richard Halls

May: Women dancing around a maypole by Aida McKenzie

June: Beach scene by Alex Dux

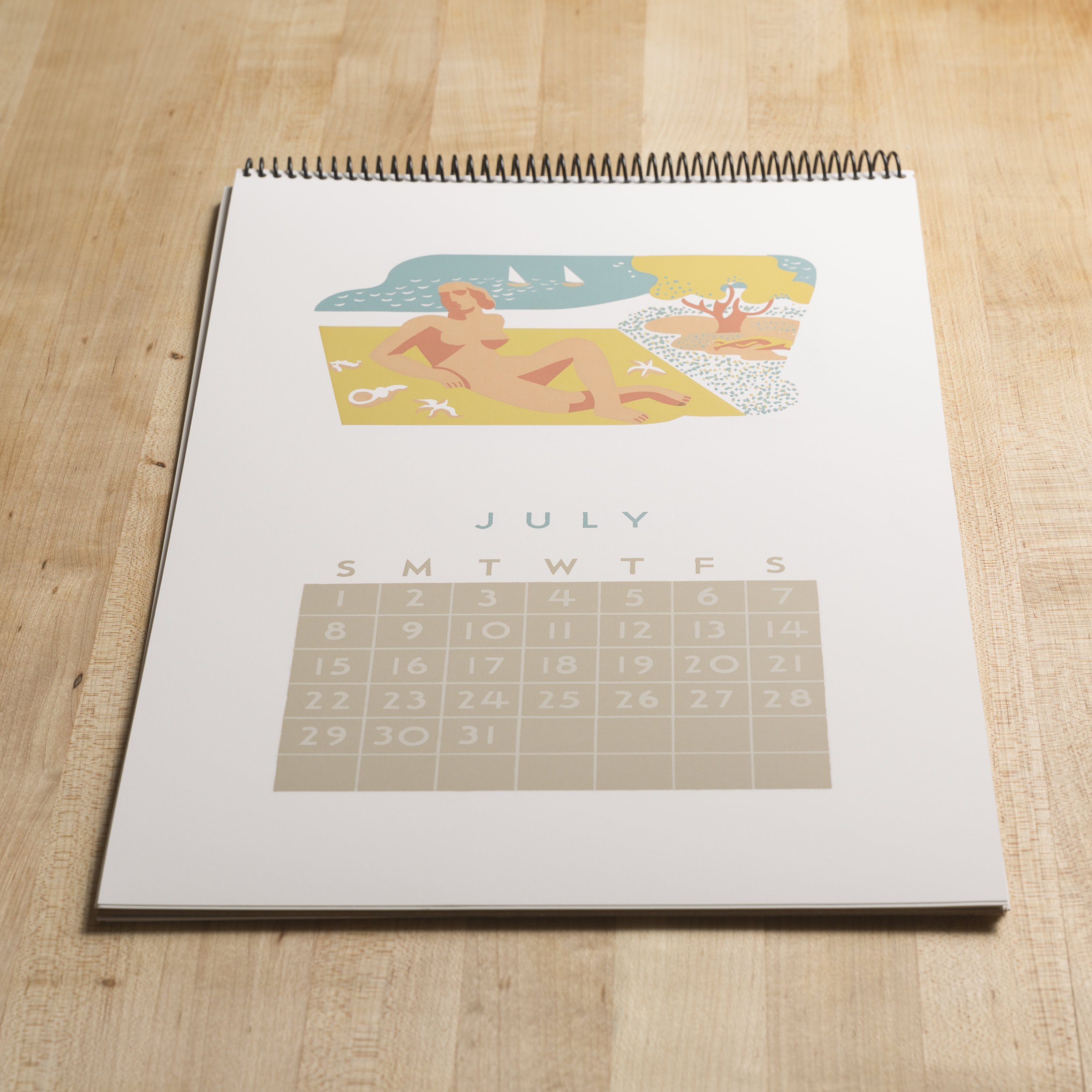

July: Sunbather by Richard Halls

August: Women harvesting wheat by Vera Bock

September: Farm scene by Richard Halls

October: Harvest scene by Bryan Burroughs

November: Hunting scene by Ben Kaplan

December: Christmas tree and rocking horse by Jerome Roth

Cover designed by Jerome Roth

Restoring for a hand-made reproduction

I captured high resolution images of each page, and carefully restored each illustration, cleaning up dust and scratches while trying to retain the character of the original silkscreen print.

Rearranging the date grids for 2018, I’ve created a new hand-made reproduction that’s slightly larger than the original to show off the beautiful artwork. Each calendar is assembled and bound by hand, printed with archival pigment inks on acid-free fine art paper, reminiscent of what the original stock would have looked like before nearly 80 years had passed.

I’ve also arranged all twelve illustrations on a poster printed on the same archival paper. I love seeing all twelve scenes together, noticing how the colors progress through the seasons represented in the artwork. This print looks great on a wall.

The 11×17-inch calendar is available as an open edition, but the 18×24-inch print is limited to an edition of 250, and each poster print is hand numbered.

Government-funded art and the origins of the New York City Poster Division

“The real success… of aid to the creative ones among us, is in… what that does to the nation’s mind to coax the soul of America back to life.”

The calendar—and the New York City Poster Division where it was designed—represent the fulfillment of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s goal in establishing the Works Progress Administration and its projects. In 1935, the WPA was formed as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal Administration. The idea was to create jobs for Americans who lost theirs in the Great Depression.

“The Great Depression fostered a generation of young people in New York City who knew what they were about because evidently their elders didn’t.”

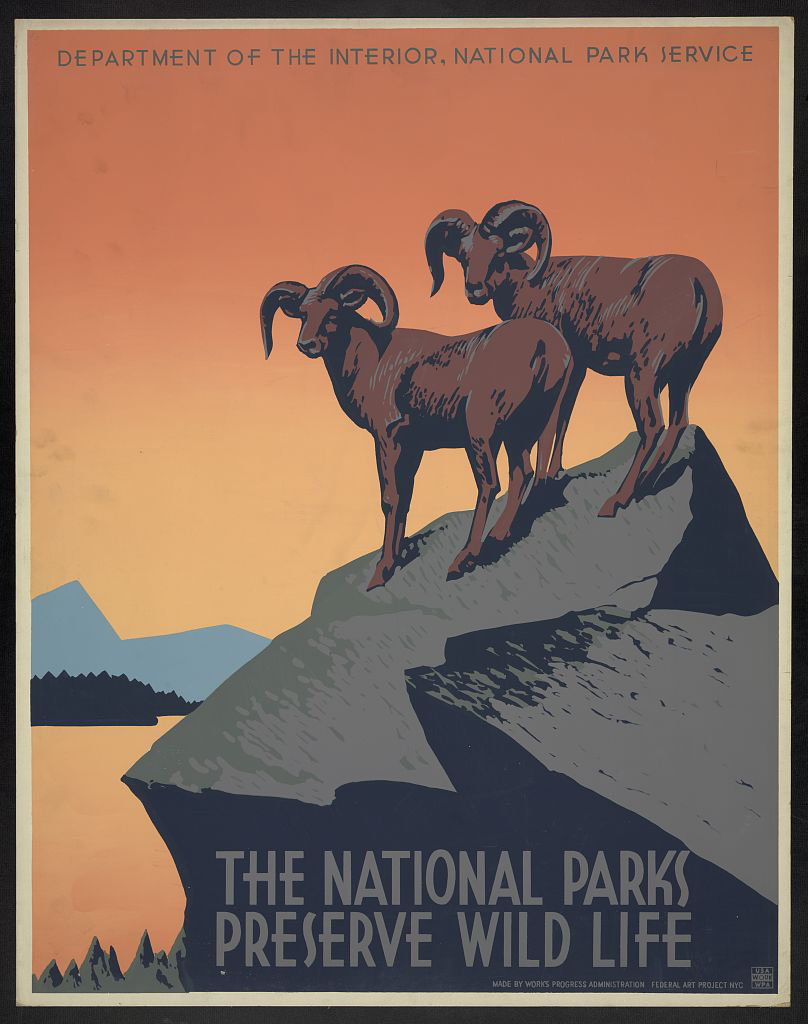

One part of the WPA, the Federal Art Project, employed artists to create public art—murals, sculptures, paintings, photographs, posters, and more. Around 10,000 artists were supported by the Federal Art Project, including many who were or would go on to become renowned such as: Berenice Abbott, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, Diego Rivera, and Mark Rothko. Some 200,000 unique works came out of the Federal Art Project, and it became a model for future efforts of Government support for the arts, like the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities.

“It is necessary and appropriate for the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and inquiry but also the material conditions facilitating the release of this creative talent.”

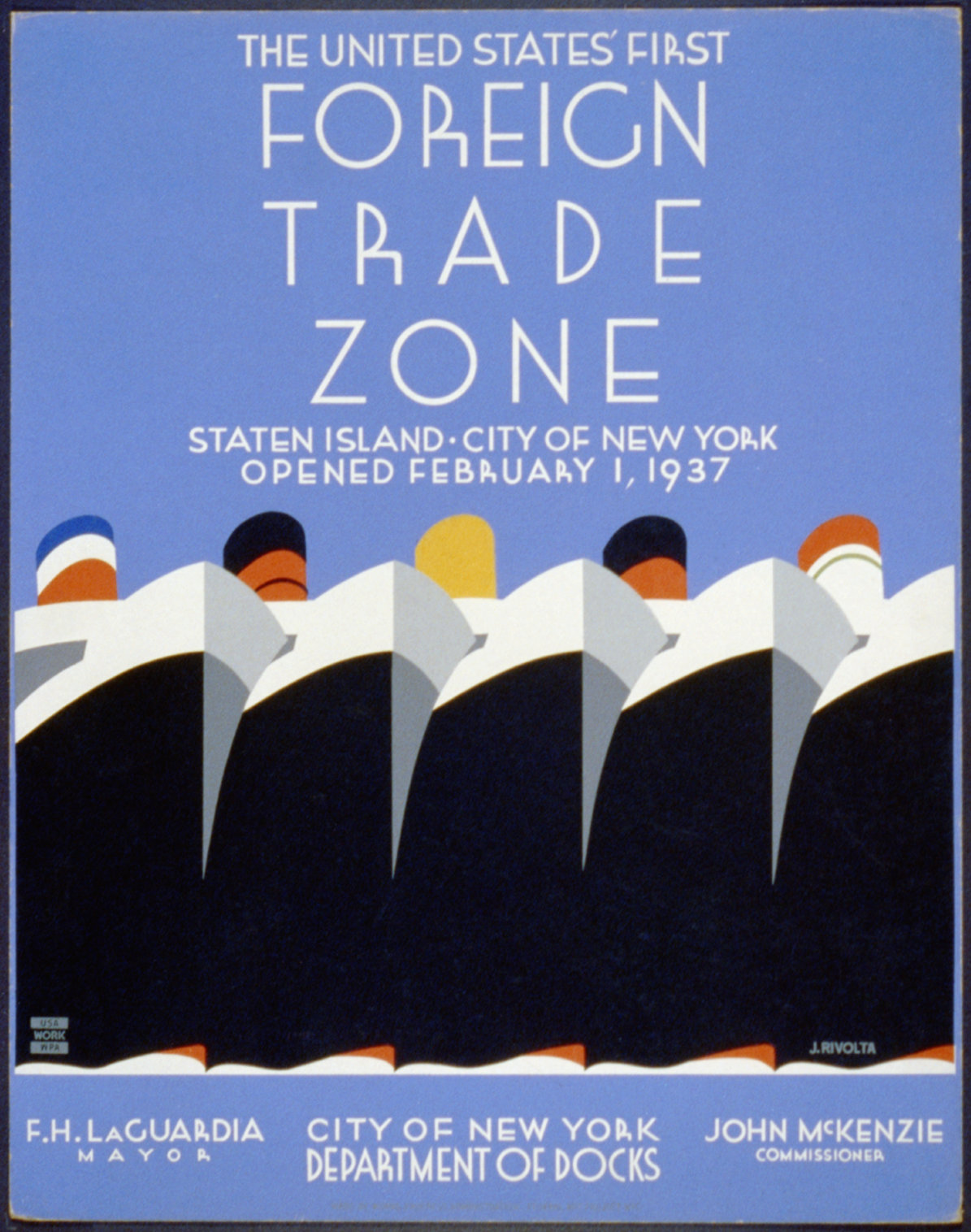

The Poster Division began as New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s Poster Project, a shop tasked with producing hand-painted posters to promote the Mayor’s various pet projects, like his anti-slot-machine campaign, and “Fish Tuesday” to boost the local fishing economy. The first Poster Division formed when the federal government took over the Mayor’s poster department in 1935.

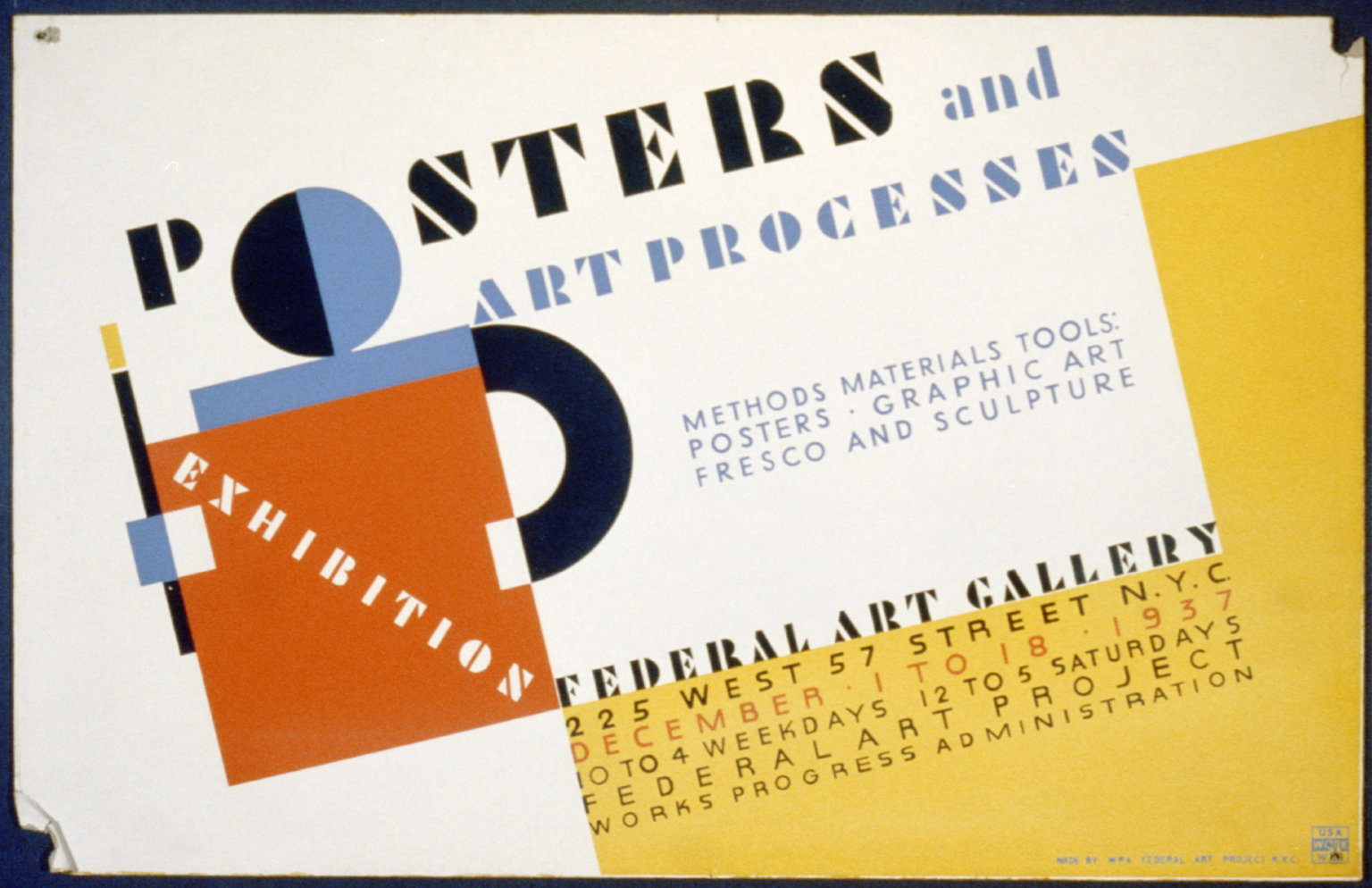

At first, all the posters were hand-painted, with any duplicates carefully hand-copied—a tedious process that limited the Poster Division’s scope and output. One of the artists, Anthony Velonis, had previously worked in a department store, where he produced show cards for window displays and countertops using silkscreen printing, a commercial printing technique that up to that point was used for short-run items like cards, banners, and signs. Silkscreening was fast and economical for products that required only a few copies, but it remained a strictly commercial process.

Silkscreened posters as a new art form

Velonis thought that the techniques he had learned in his work as a silkscreen printer would be of use in the Poster Division, allowing them to produce more copies in less time. He got approval to set up a small workshop in one of the upper floors of the General Electric Building at 51st Street and Lexington Avenue, and he and other artists began producing simple one- or two-color posters while developing their technique. As the artists became more familiar with the process, the posters grew in complexity, and the shop was soon producing six- to eight-color posters at a rate of 600 per day. The workshop became so successful that it moved locations several times, ending up at 110 King Street alongside the rest of the NYC Federal Art Project workshops and administrative offices.

The Poster Division made its services available to any public agency that could use a poster, and Velonis continued to improve his techniques and processes, treating silkscreen printing with the same care as painting or any other visual art. He coined the term Serigraphy as a name for printing multi-colored fine art using advanced silkscreen printing techniques, and he produced manuals and led workshops in other cities.

“The finished work must convey the feeling that the artist has a certain amount of intimacy with his printing medium, no matter how mechanical.”

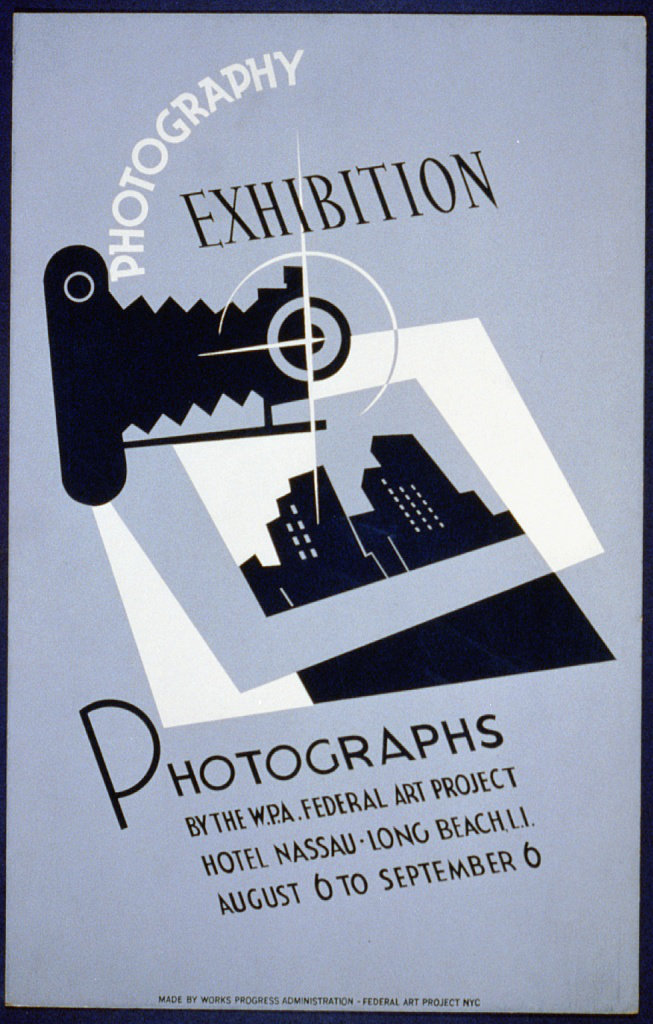

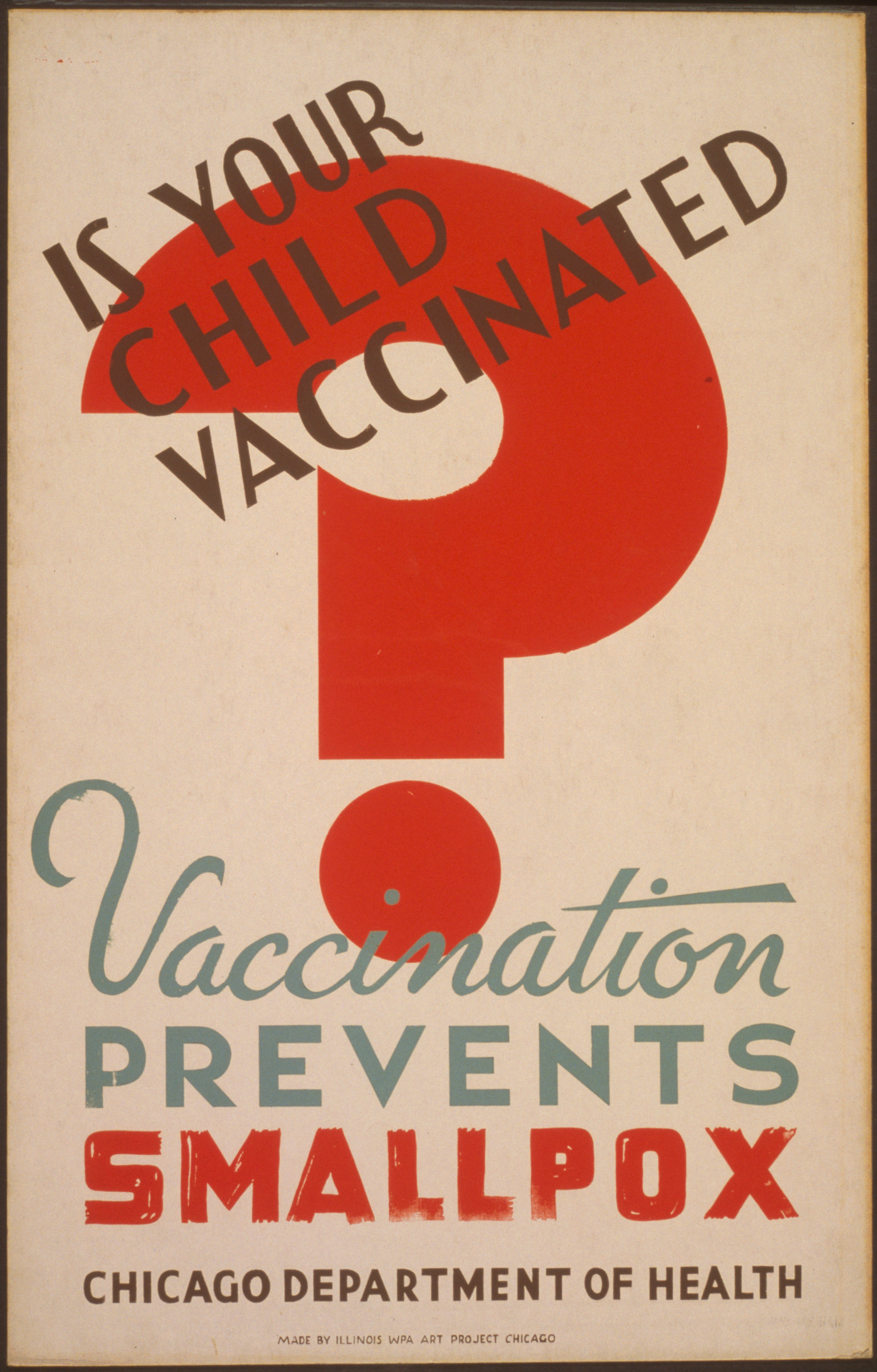

By 1938, Federal Art Project Poster Divisions existed in at least eighteen states, creating posters for any government agency that wanted posters for any purpose—“civic activities, band concerts, lectures, and Federal Theatre Project productions; others informed citizens about health-care problems and treatment centers.”

“The poster provides the same service as the newspaper, the radio, and the movies, and is as powerful an organ of information, at the same time providing an enjoyable visual experience.”

Democratic art

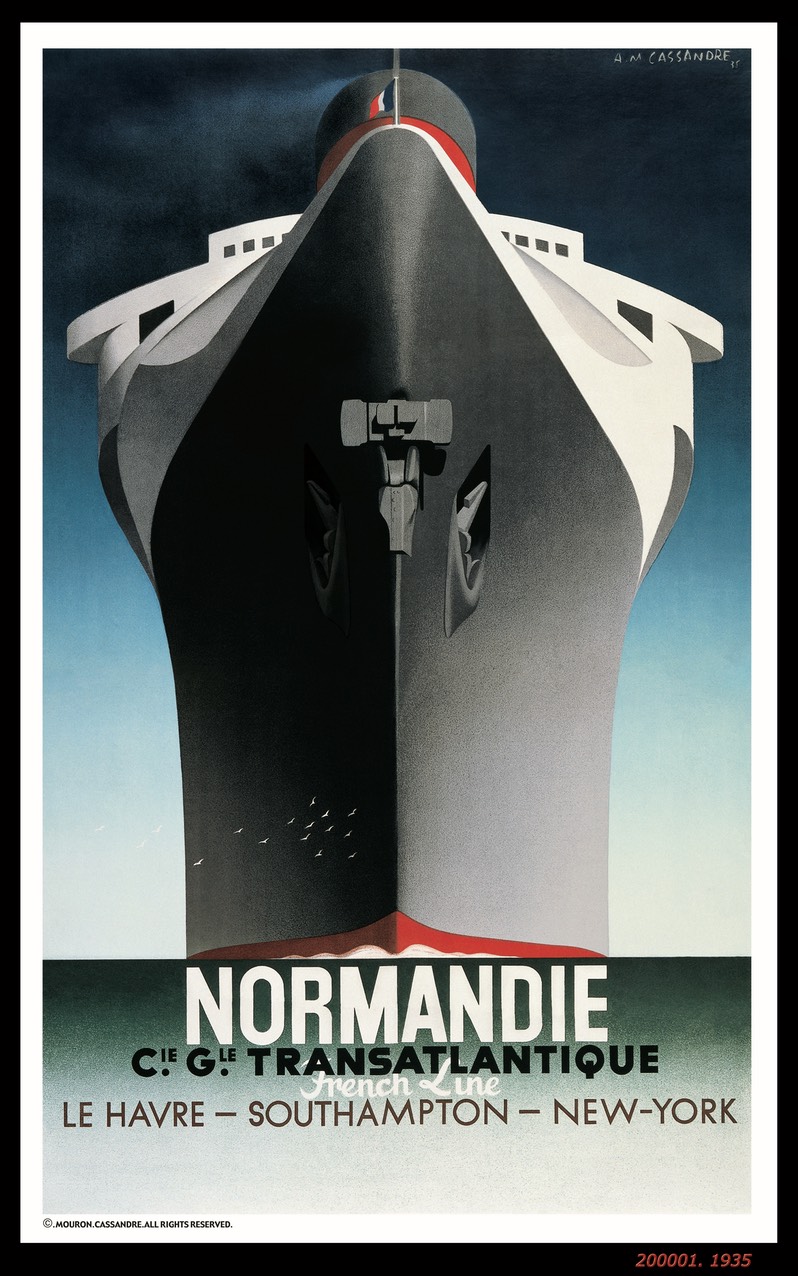

Poster artists working for government clients weren’t worried about producing profits through advertising, thus “artists experienced an unprecedented freedom to experiment with typography, colors, visual styles, and techniques, freely applying concepts of design derived from abstract, Constructivist, and Bauhaus principles.” The techniques and styles that the artists used were heavily influenced by modern and contemporary design coming from Europe—like travel posters by the french artist Cassandre—and the designs were often far ahead of what other commercial artists and advertising agencies were producing at the time.

NYC Poster Division Director Richard Floethe was largely responsible for the division’s design sensibility. Floethe emigrated from Germany where he had trained at the Bauhaus school, studying design with Paul Klee and color theory and composition with Wassily Kandinsky.

Floethe fostered a spirit of collaboration among the artists—anyone could propose concepts for any project that came in, and concepts were reviewed, critiqued, and voted on to proceed through the design process. This encouraged collaboration and interaction across divisions of the Federal Art Project, too—painters and moralists would often collaborate on concepts as they passed through the workshop—one third of the Federal Art Project’s artists were in New York City.

“I had decided early that I would learn as such as I could from everybody. I felt the Federal Art Project was a golden opportunity. There had never been an art school as dynamic with so many crosscurrents.”

Opposition to publicly-funded art

Hostility toward the Federal Art Project and similar programs existed since the beginning of New Deal Administration, from critics arguing that it was a “boondoggle,” to congressmen like Representative J. Parnell Thomas, who called the Federal Writers Project “a hot bed for Communists”, and Representative Dewey Short, who argued that true art was the product of suffering artists, while “subsidized art is no art at all.” Even today, government patronage of the arts is divisive.

“Targeting waste like the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities would be a good first step…”

Concerned that the artists of the Federal Art Project were taking on social issues in their work, officials often searched their work for communist symbols and propaganda. There were ongoing attempts to hamper or shut down the Federal Art Project, including mandates to cut personnel by 25%, cap salaries at $1,000, and limit employment to 18 months. That last mandate immediately removed 70% of the artists from WPA programs.

It was in this context in 1938 that New York regional director of the Federal Art Project, Audrey McMahon, conceived of the calendar as an way to gain allies in congress and the administration, showing off the capabilities and talent of the artists employed by the Poster Divisions and the Federal Art Project. The effort failed, though, and in 1939, the Federal Art Project closed. Most of the posters and paintings produced were sold as scrap or thrown away. Today only about 2,000 Federal Art Project posters remain in known collections—0.1% of the total number of copies produced.