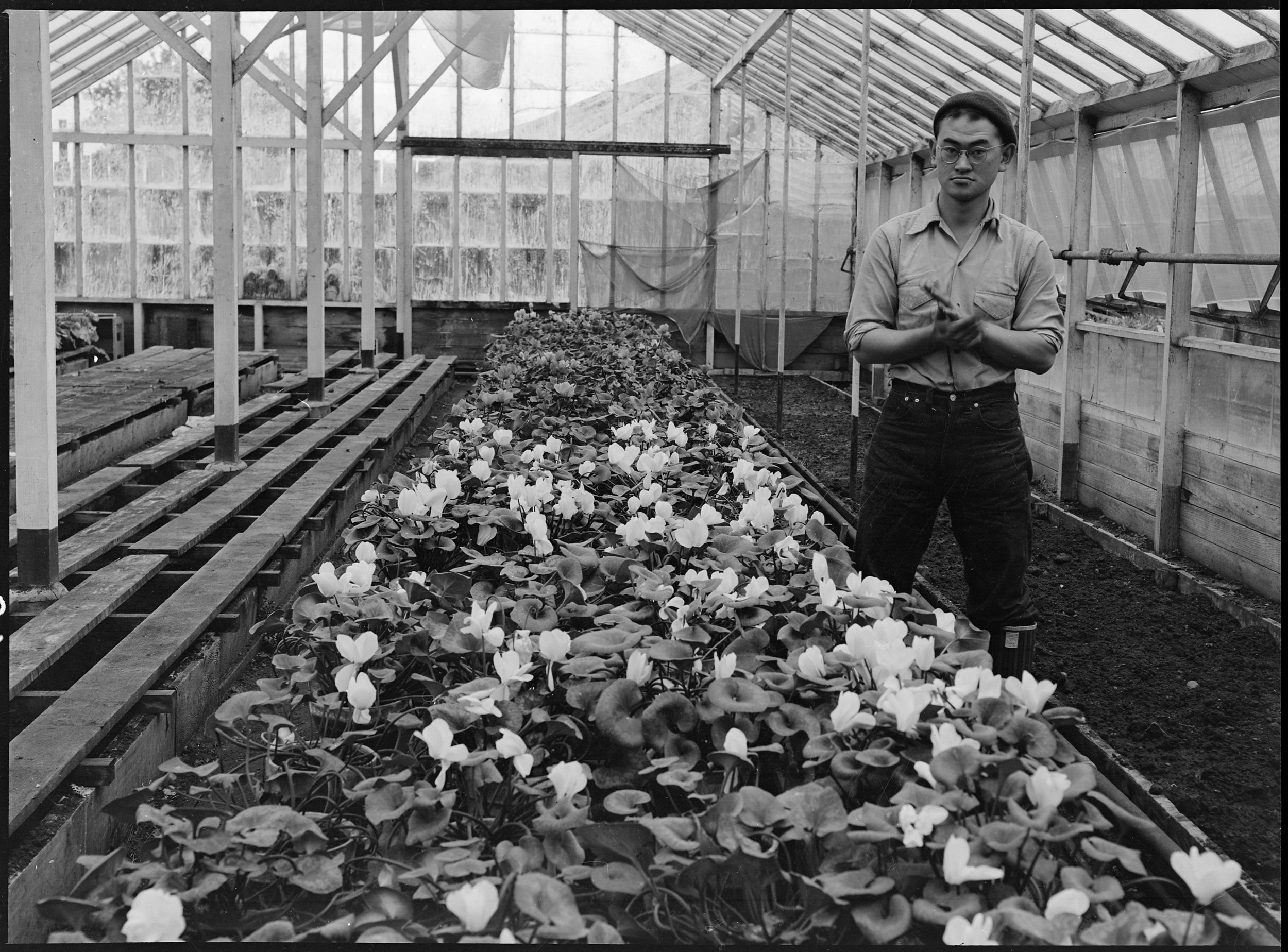

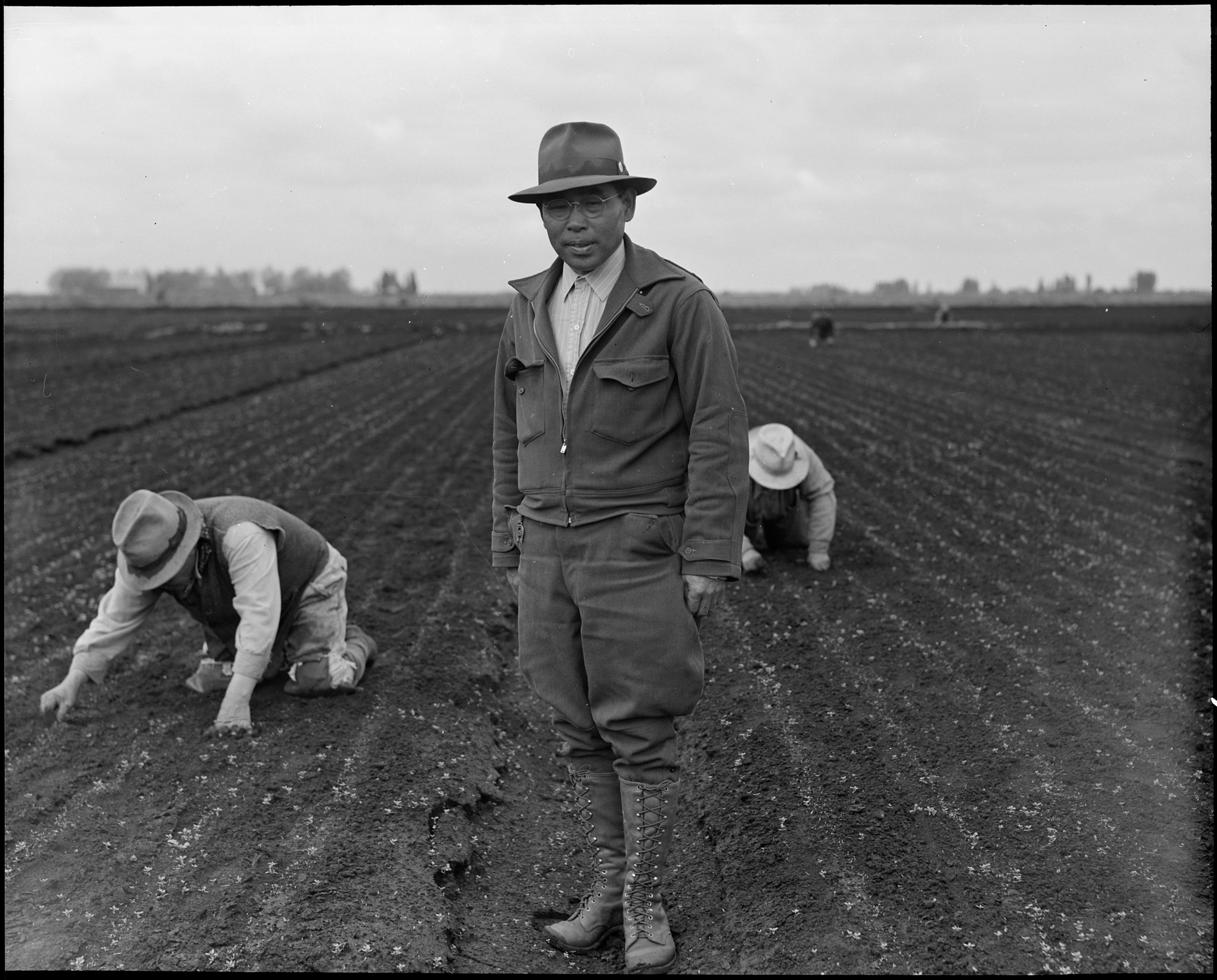

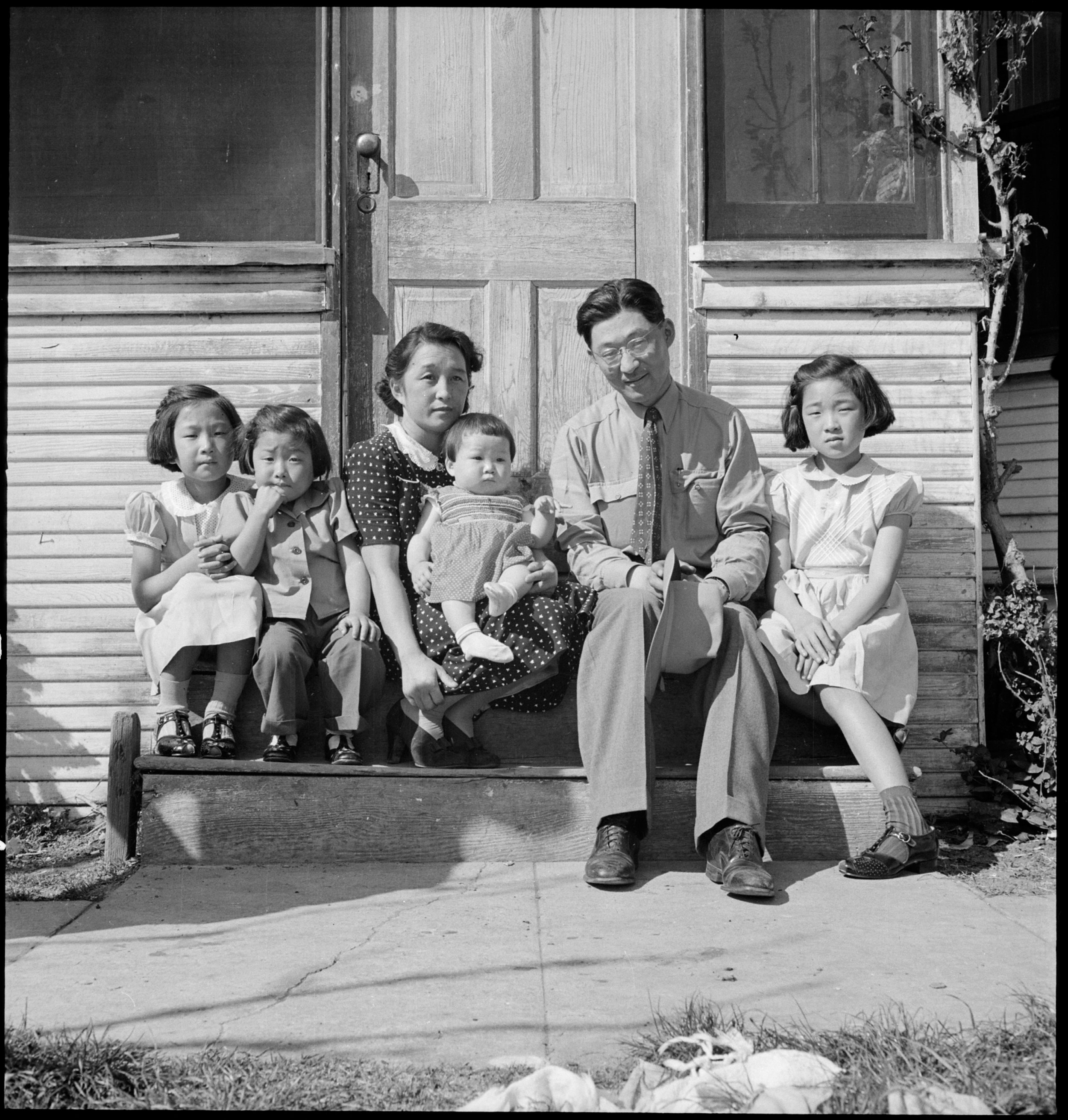

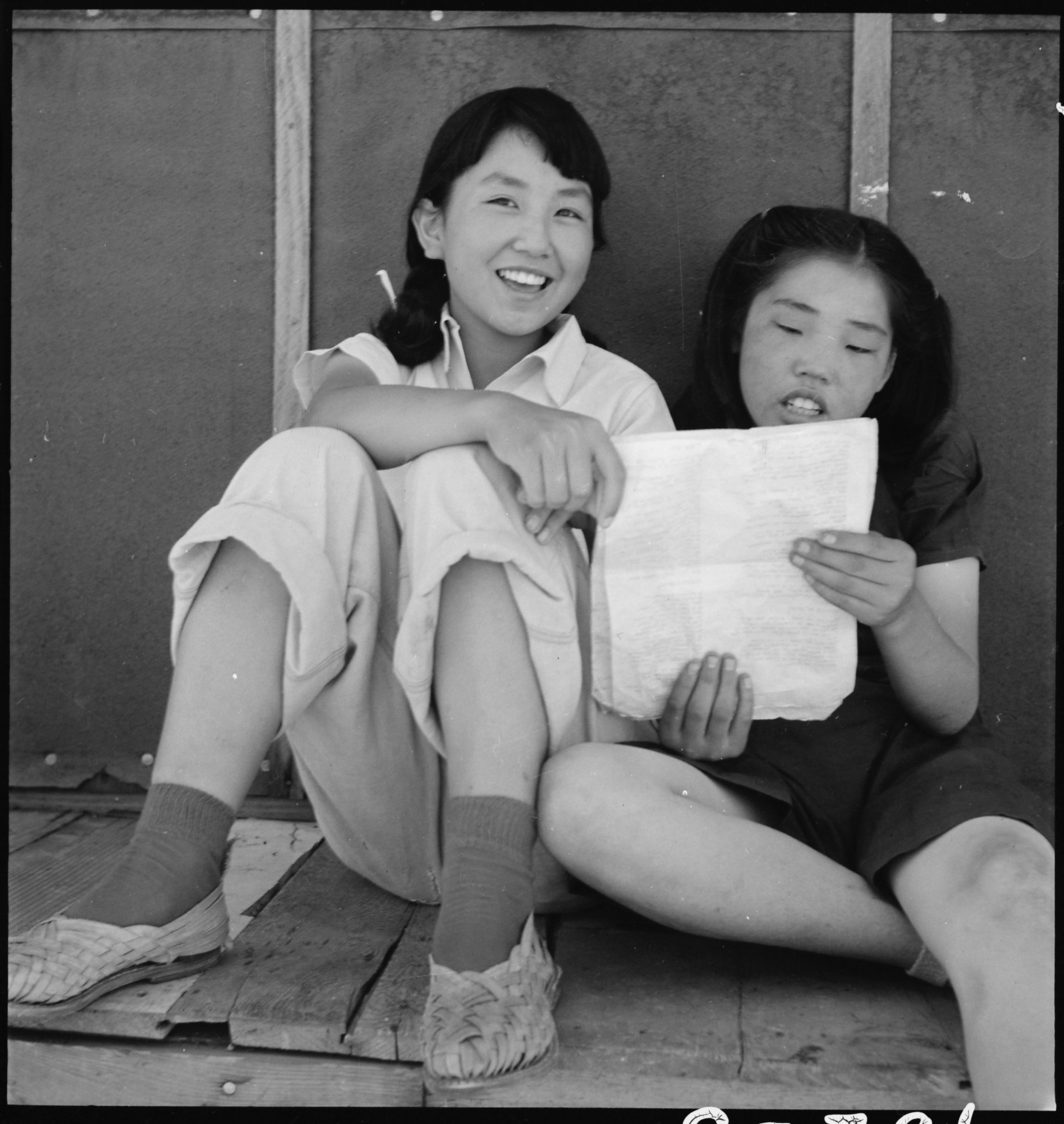

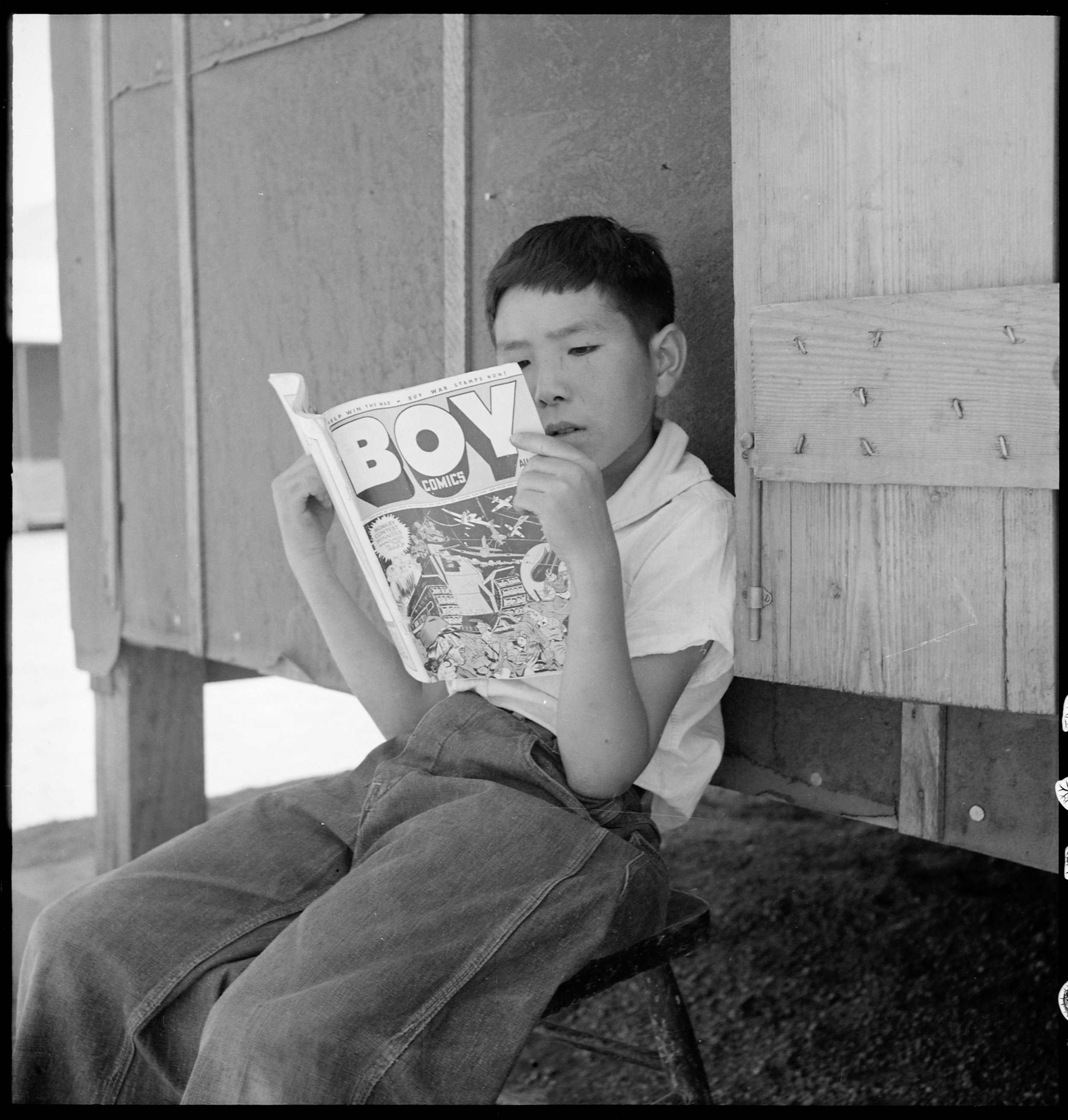

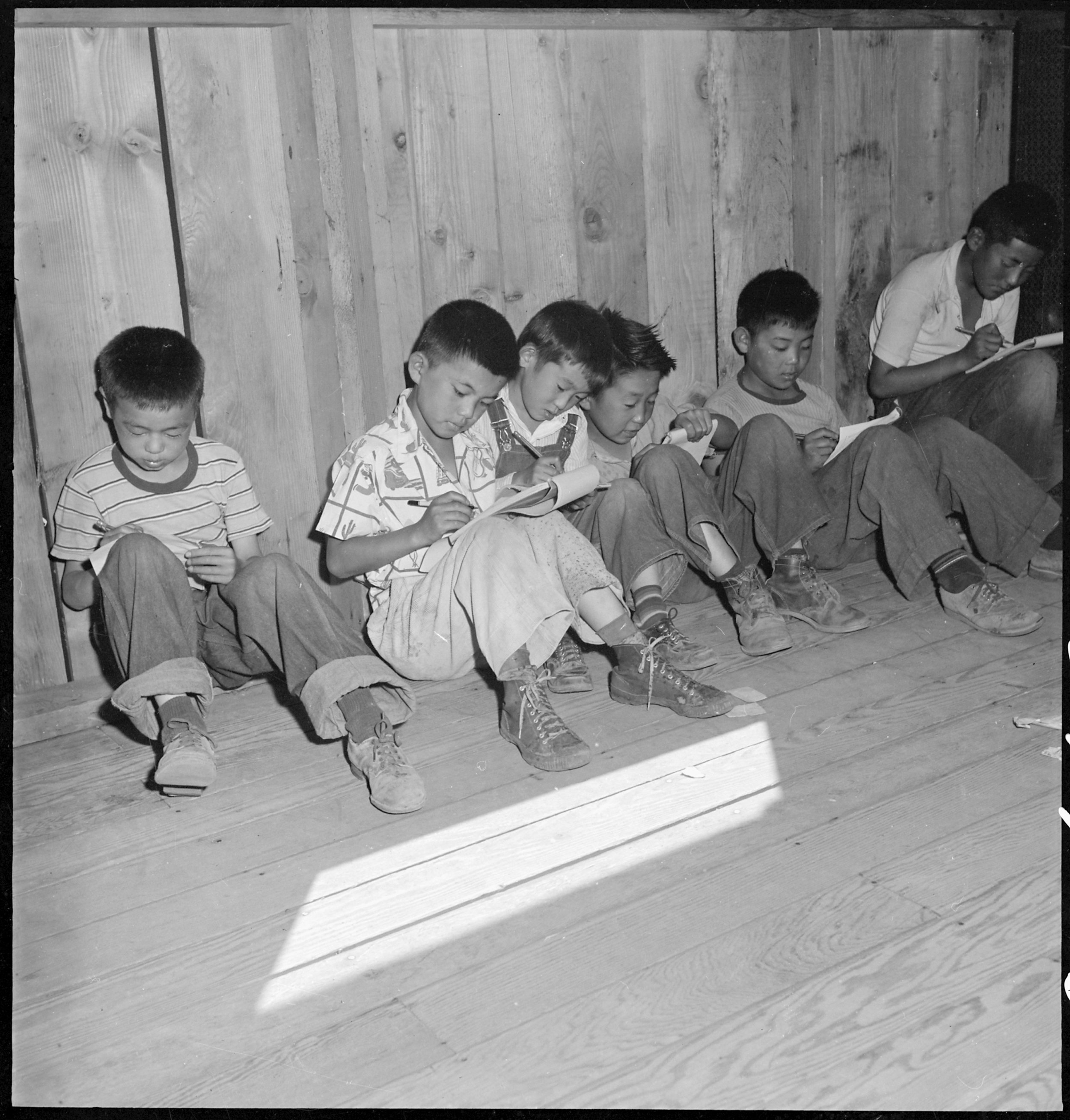

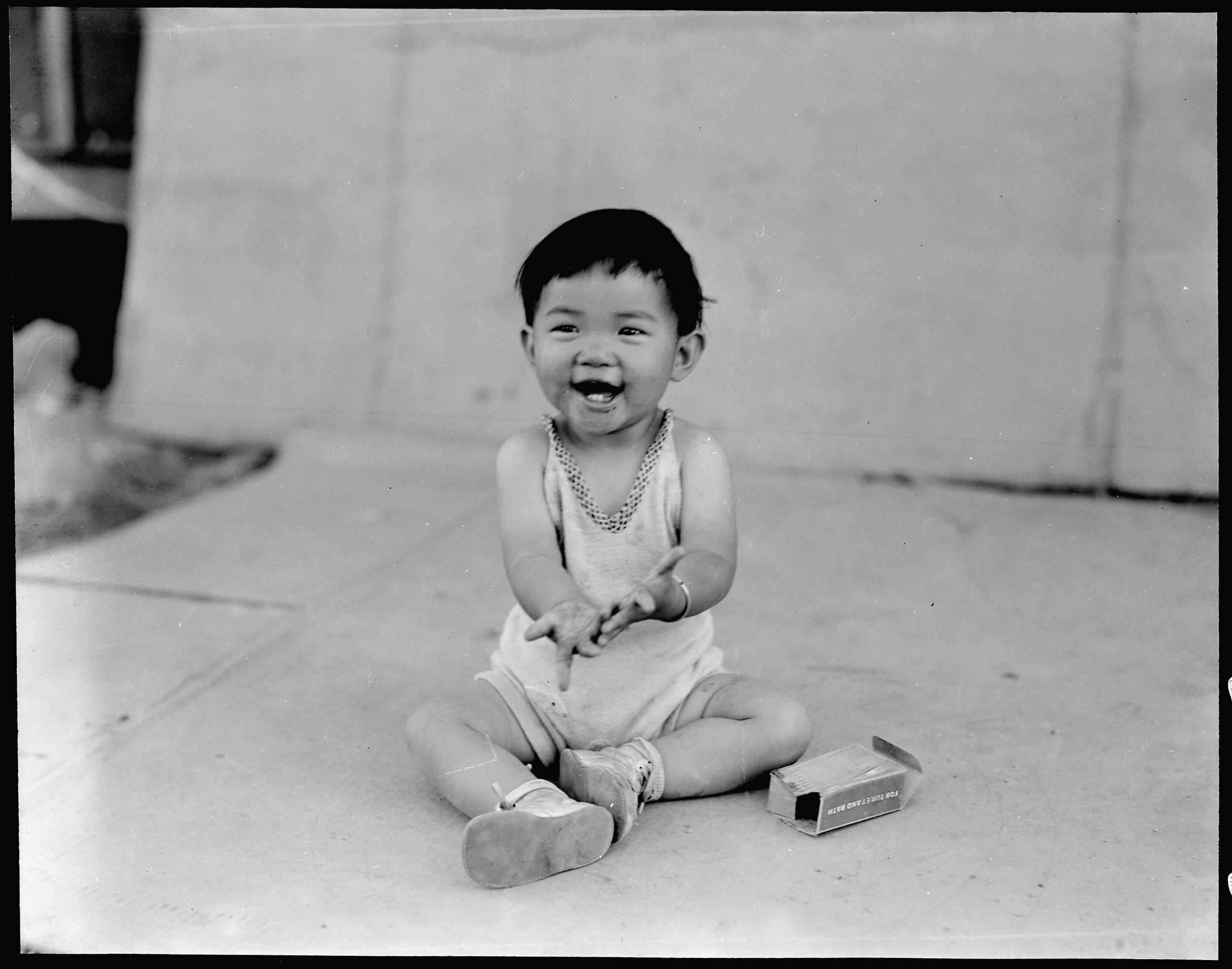

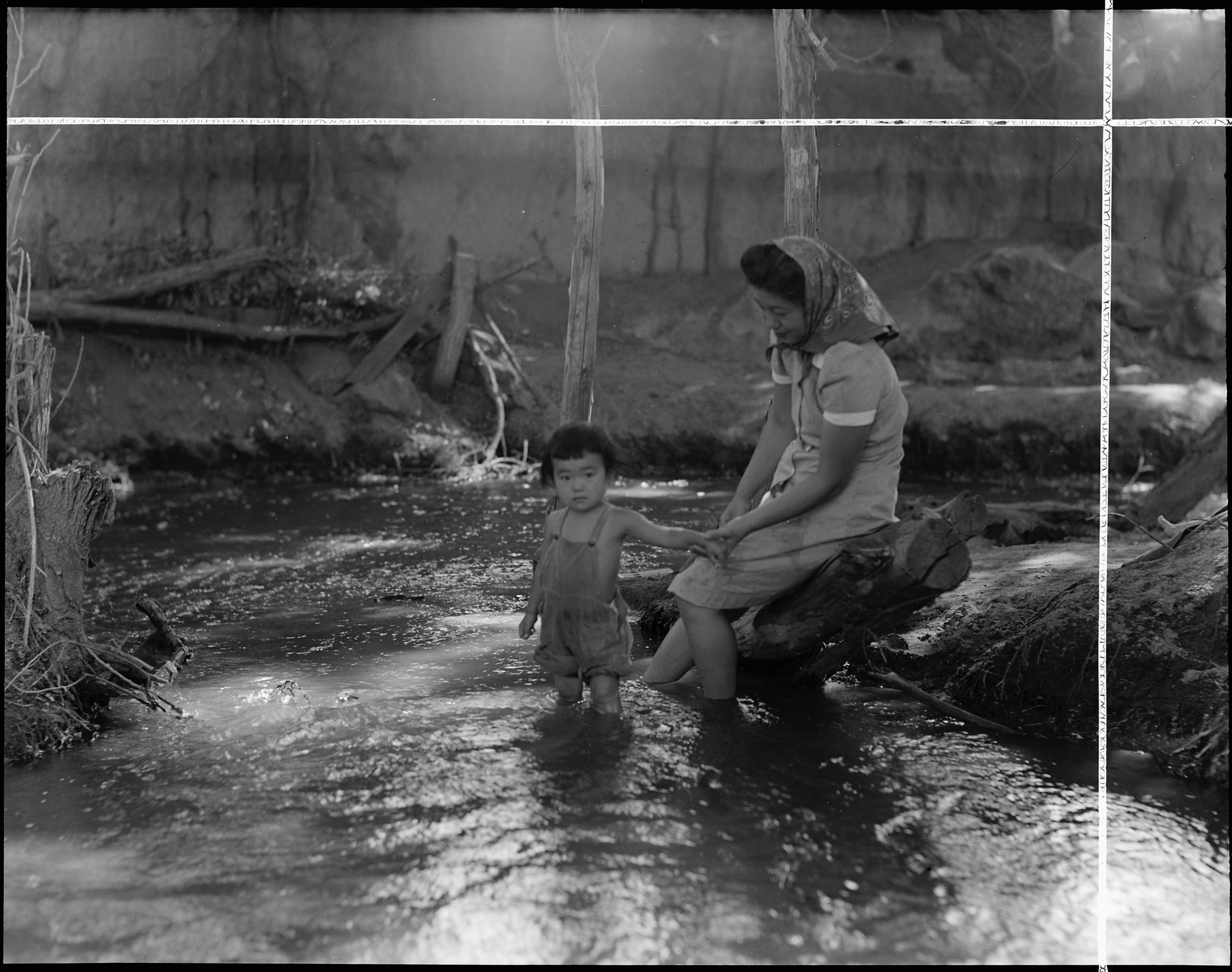

Dorothea Lange’s Censored Photographs of FDR’s Japanese Concentration Camps

The military seized her photographs, quietly depositing them in the National Archives, where they remained mostly unseen and unpublished until 2006

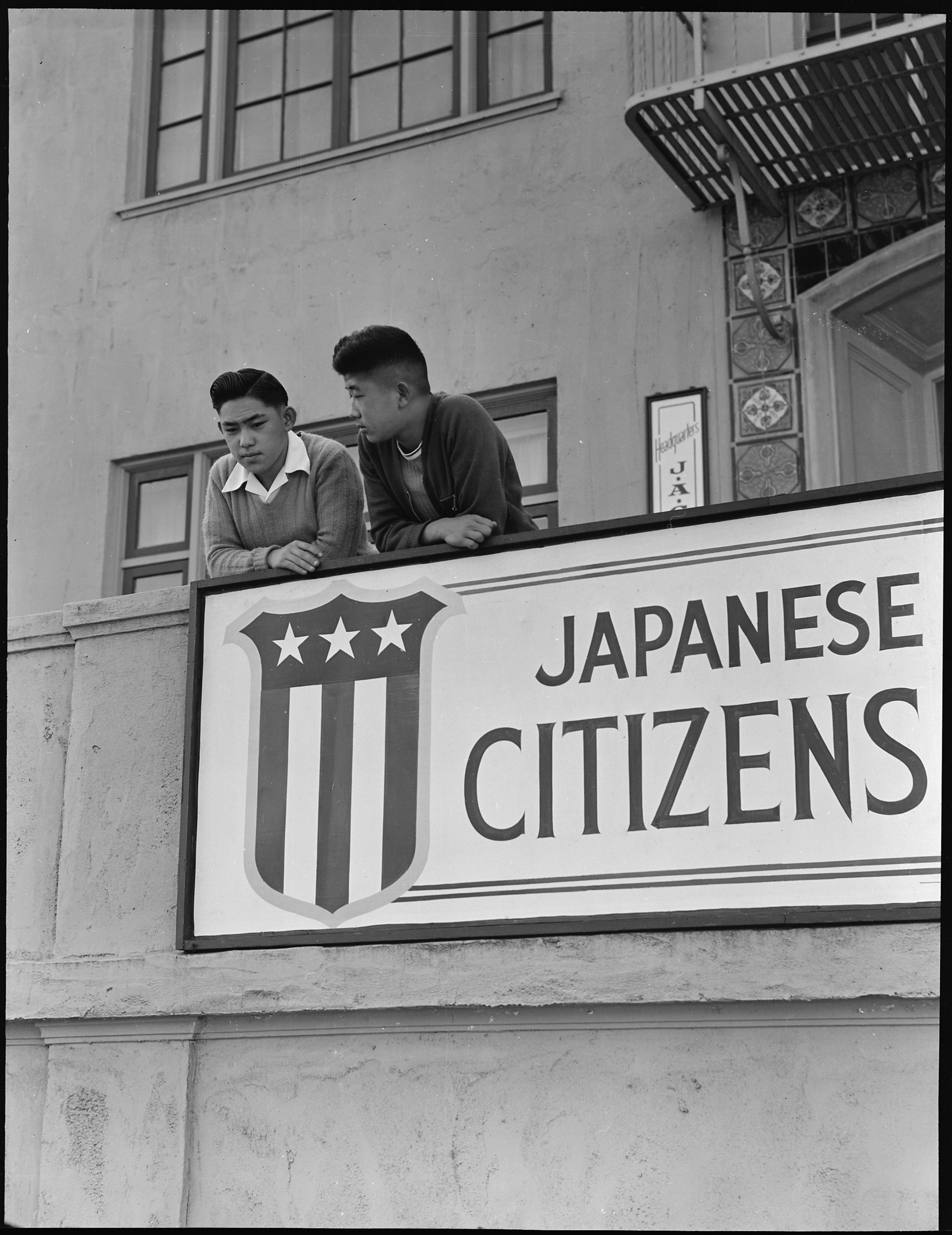

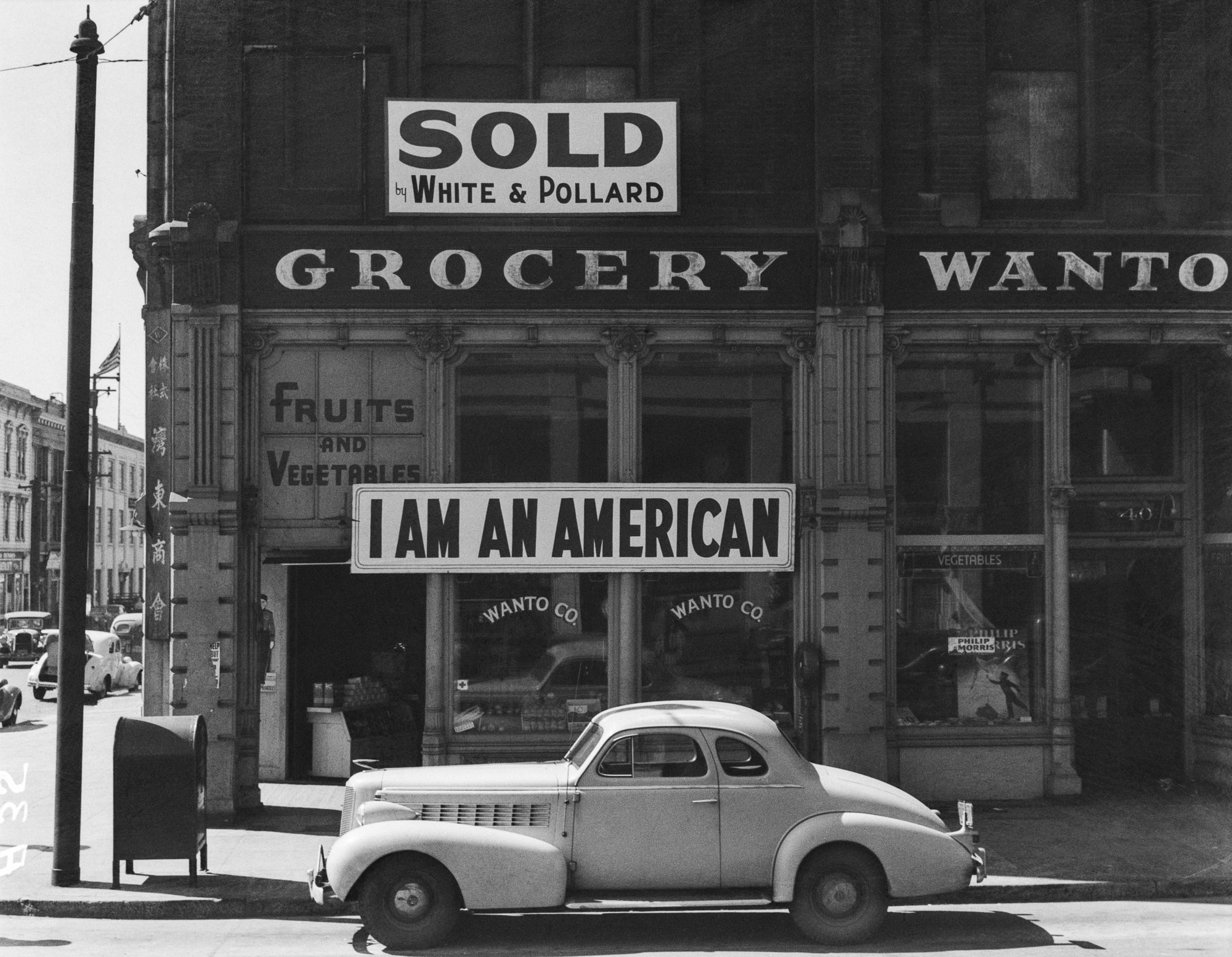

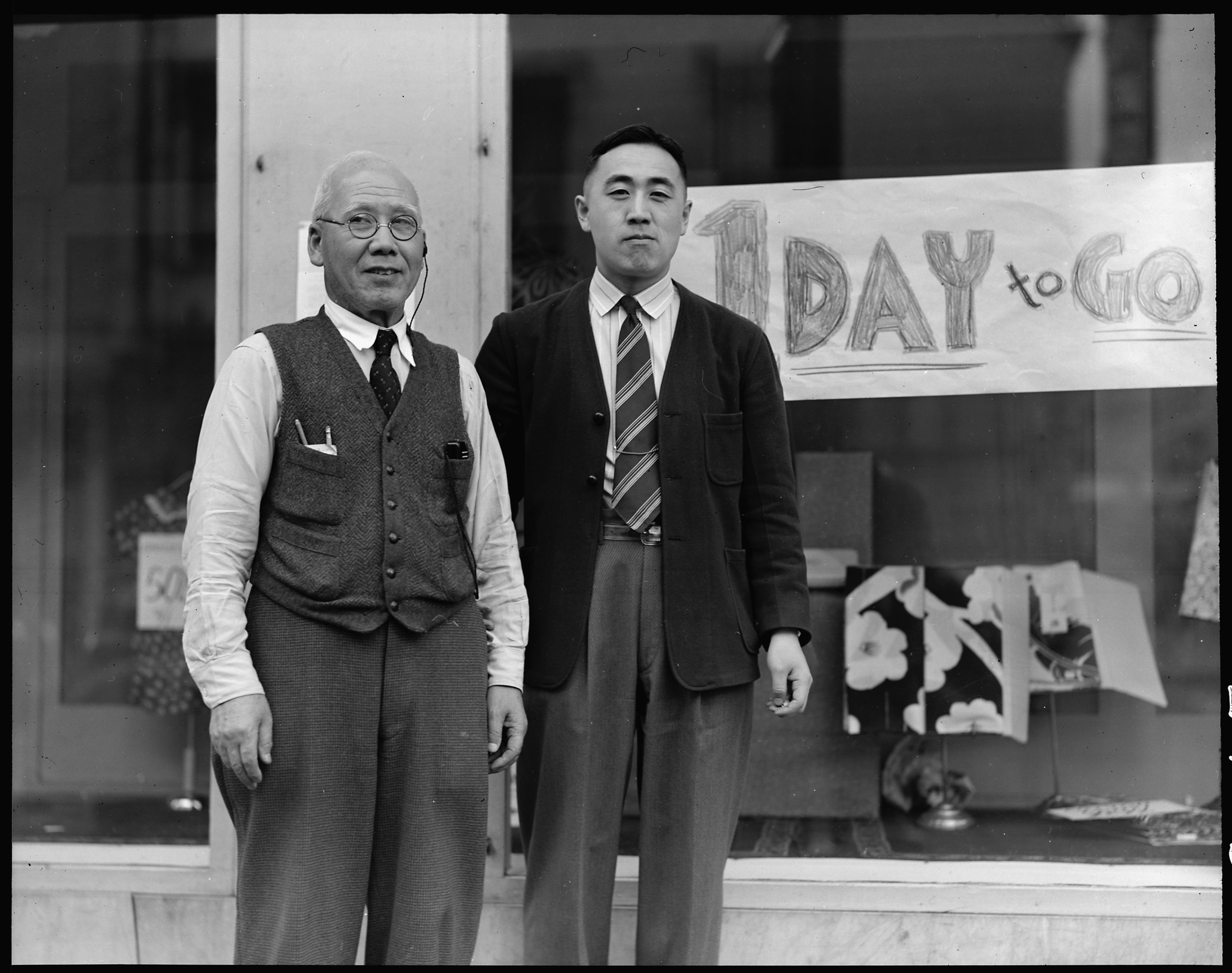

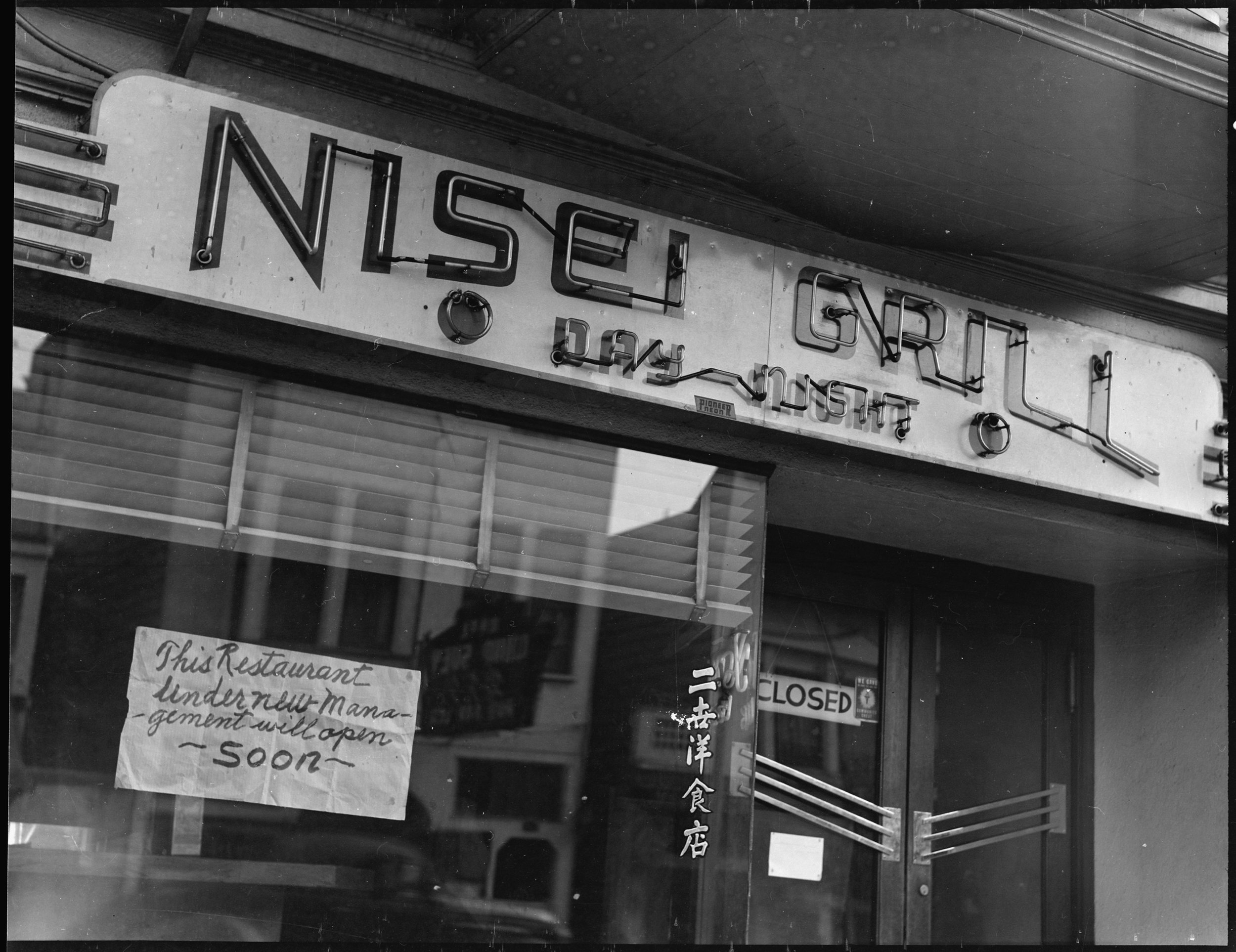

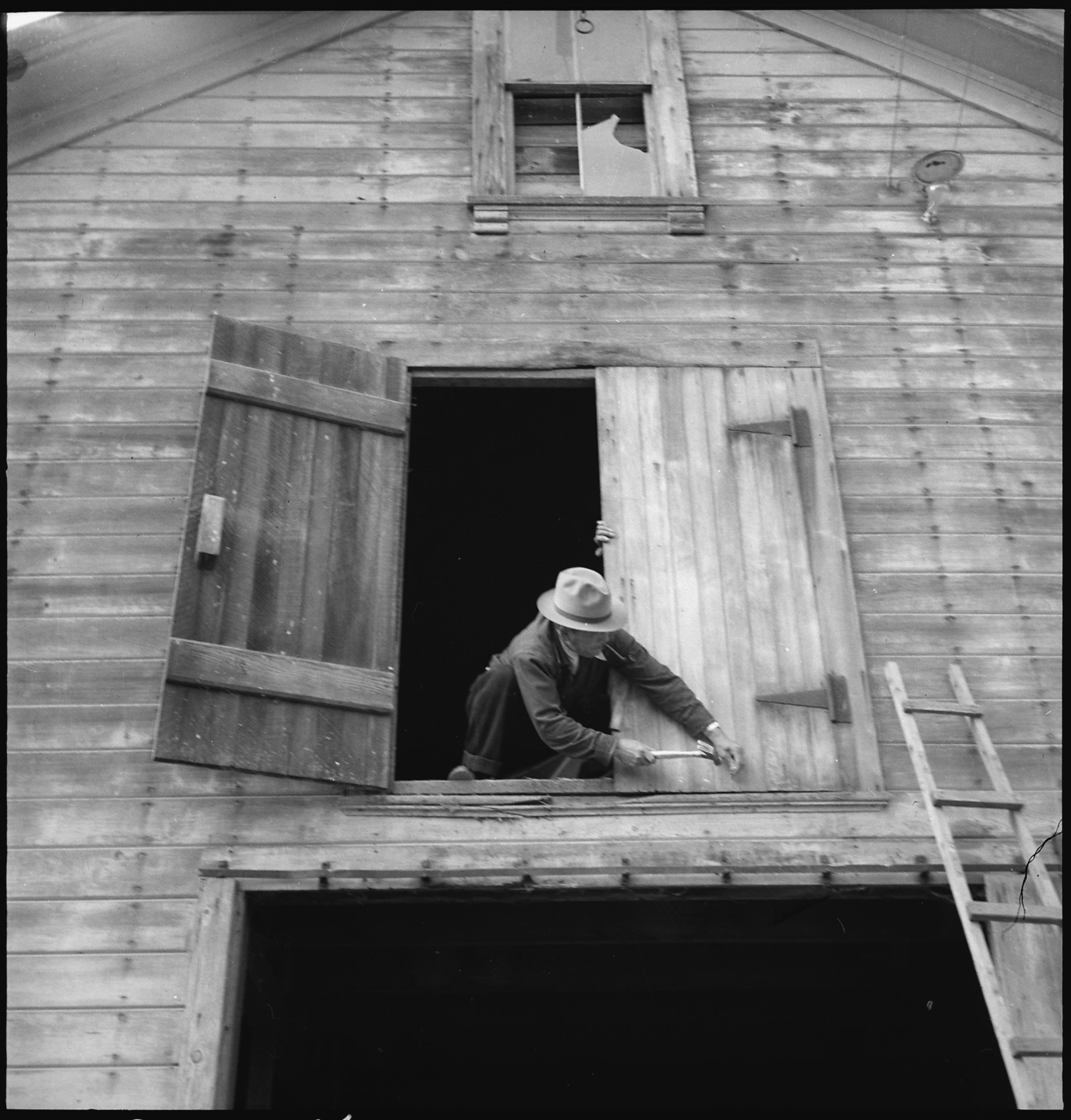

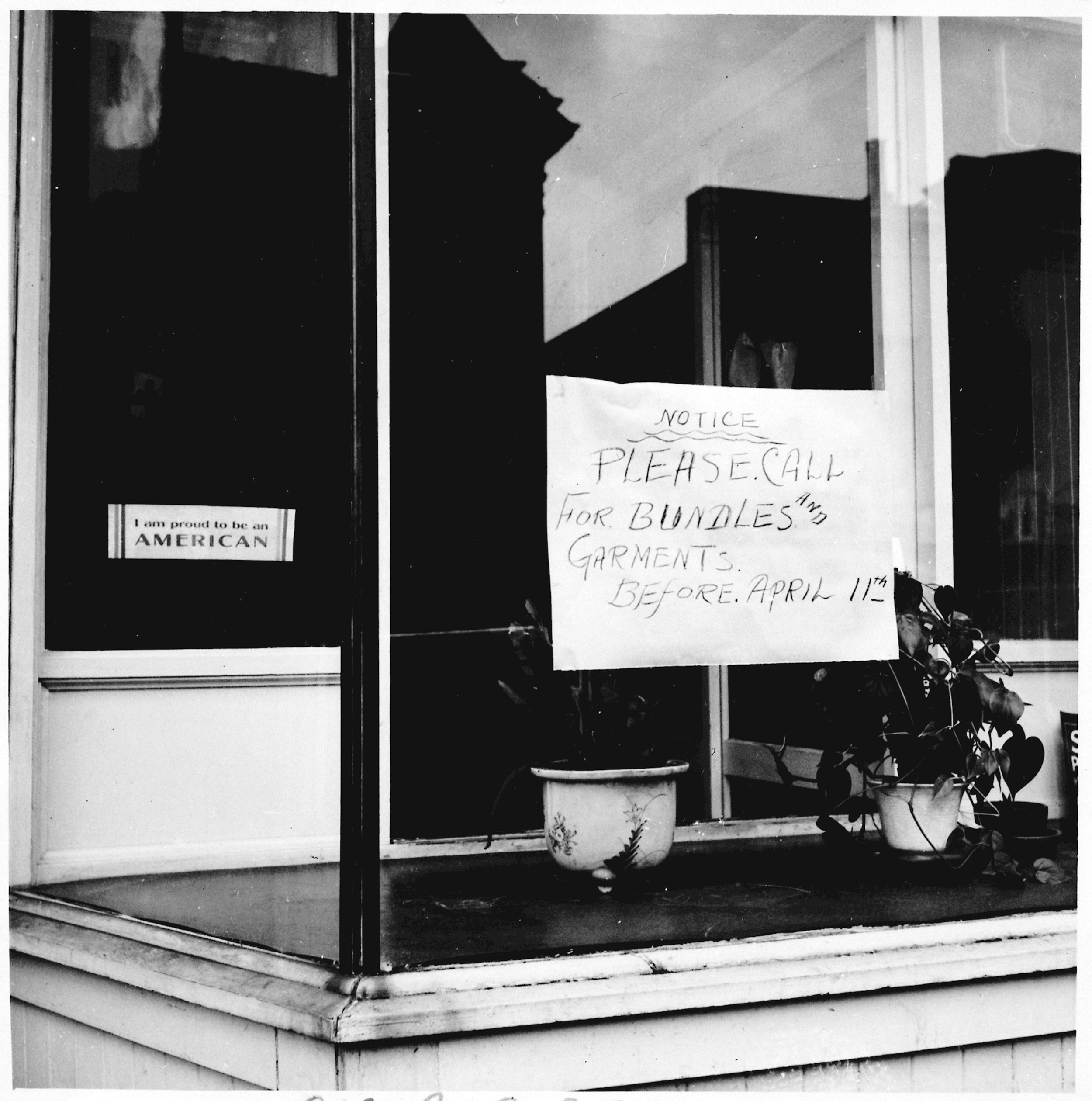

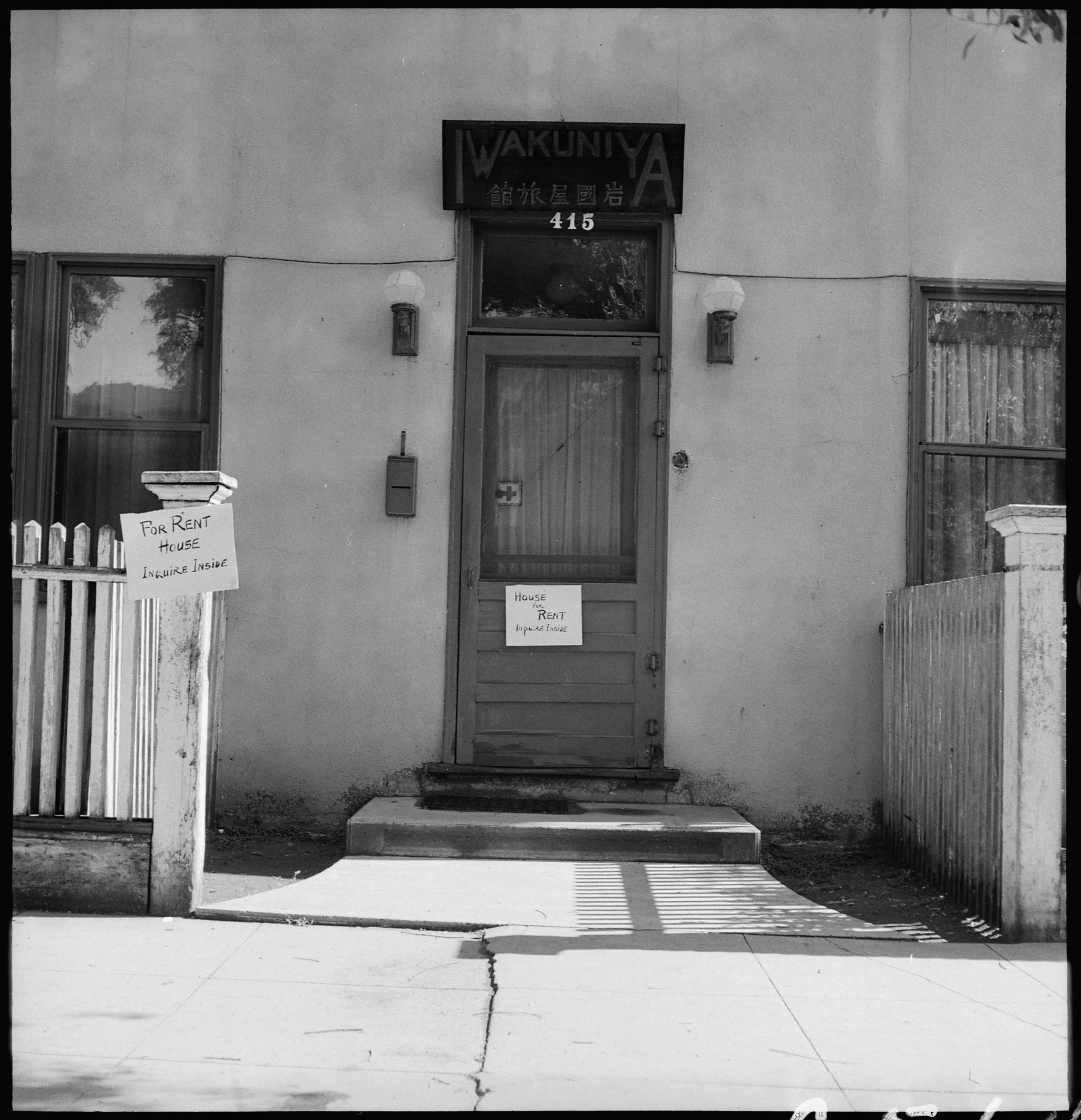

Dorothea Lange—well known for her FSA photographs like Migrant Mother—was hired by the U.S. government to make a photographic record of the “evacuation” and “relocation” of Japanese-Americans in 1942. She was eager to take the commission, despite being opposed to the effort, as she believed “a true record of the evacuation would be valuable in the future.”

The military commanders that reviewed her work realized that Lange’s contrary point of view was evident through her photographs, and seized them for the duration of World War II, even writing “Impounded” across some of the prints. The photos were quietly deposited into the National Archives, where they remained largely unseen until 2006.

I wrote more about the history of Lange’s photos and President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 initiating the Japanese Internment in another post on the Anchor Editions Blog.

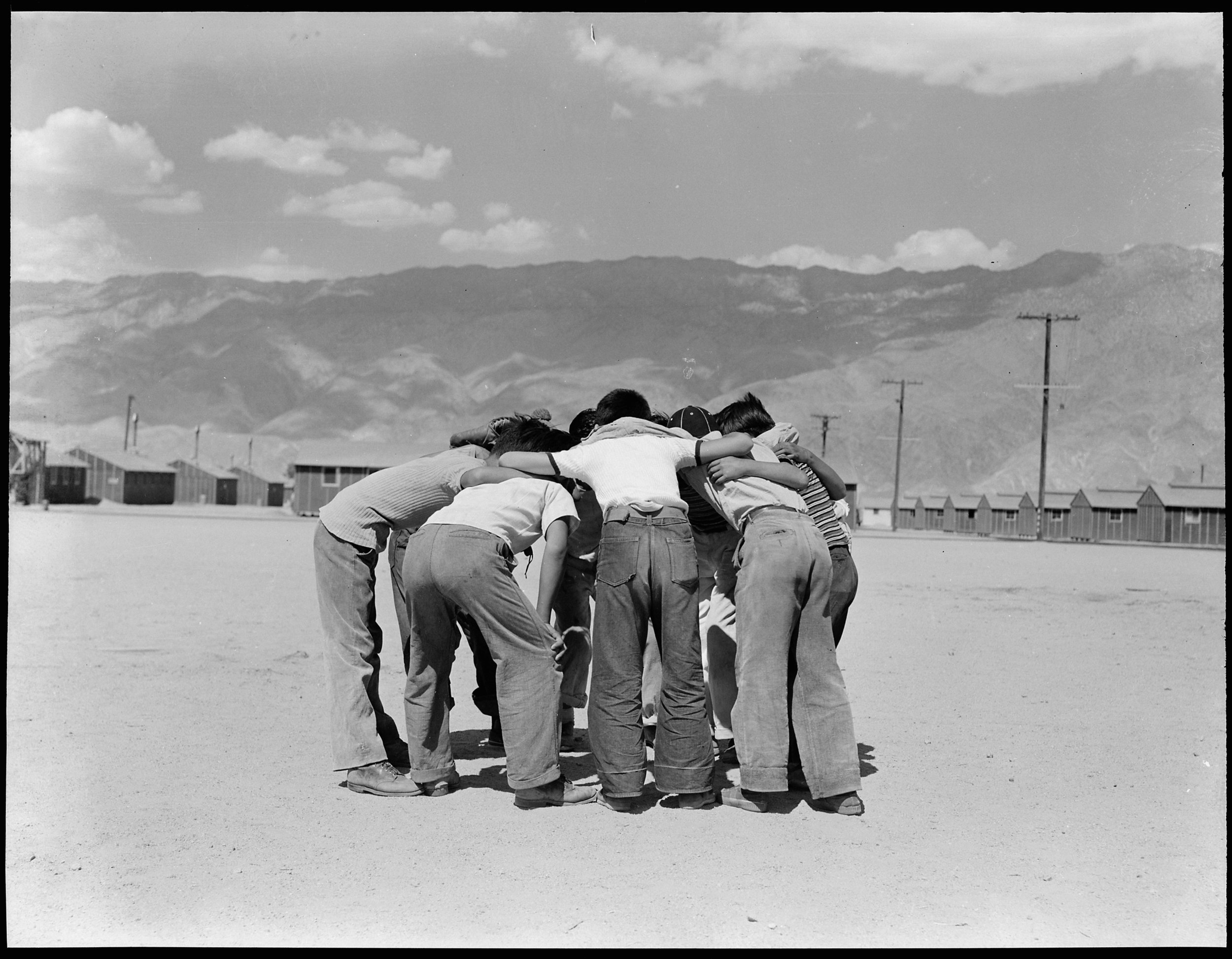

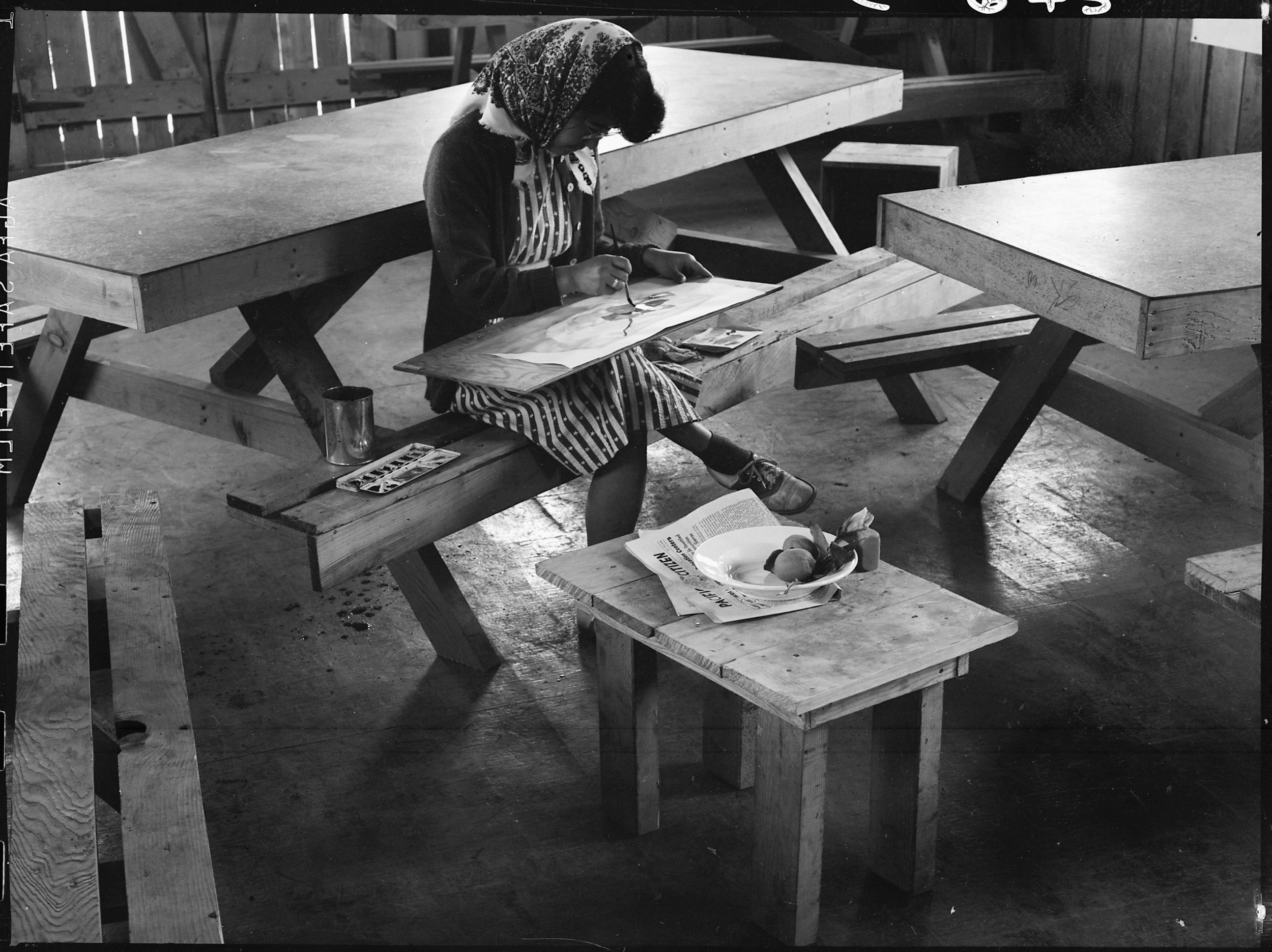

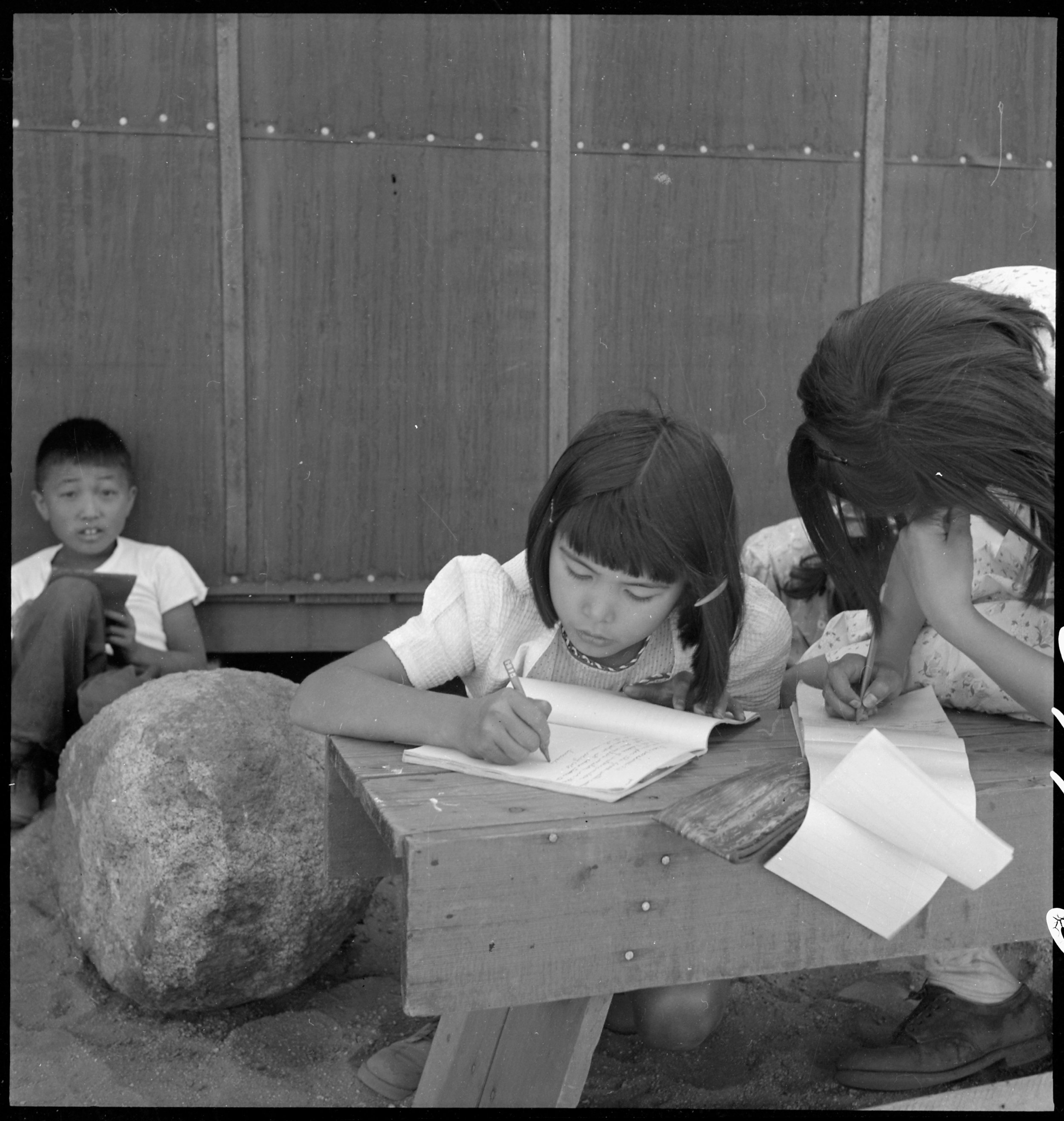

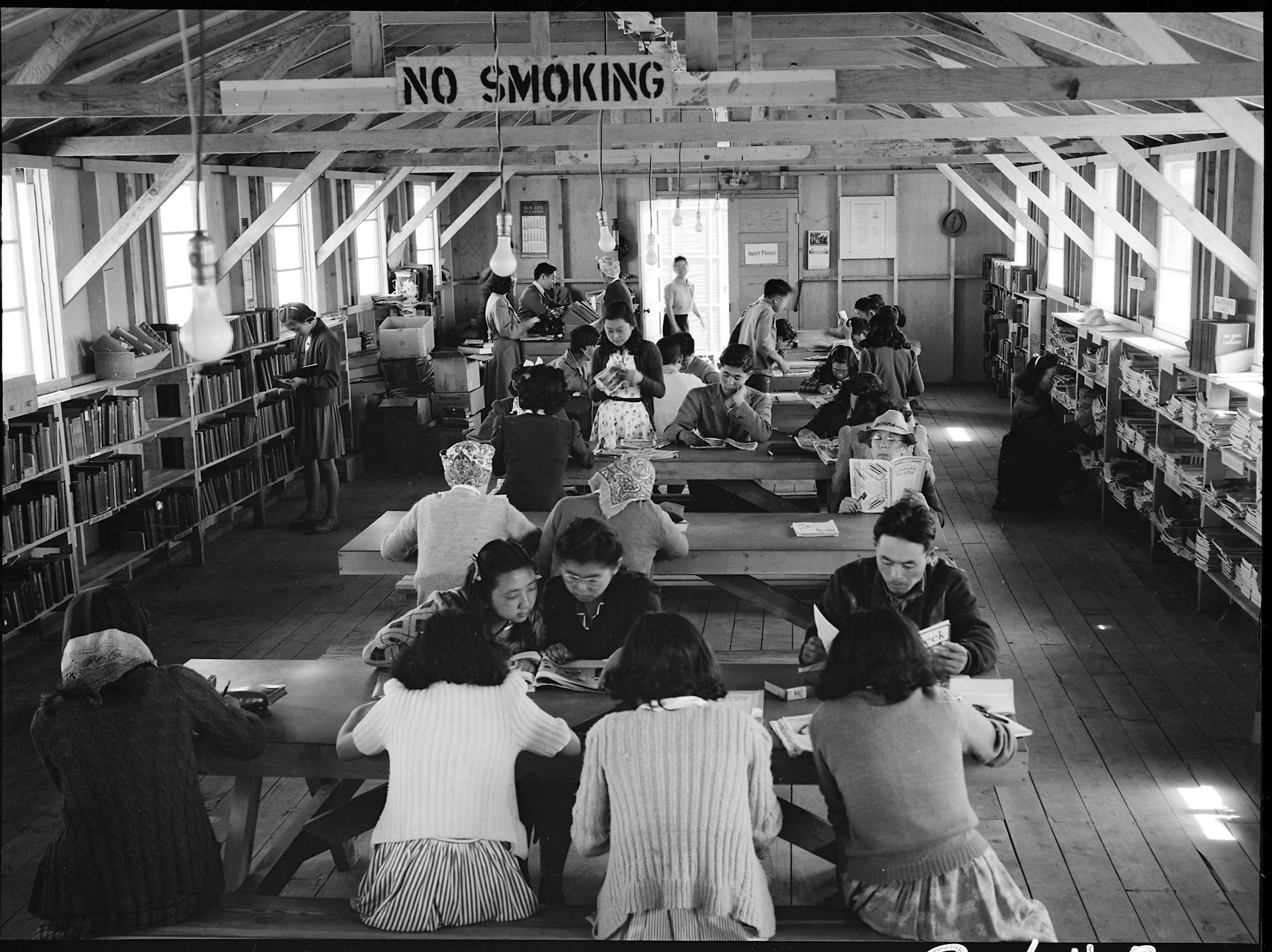

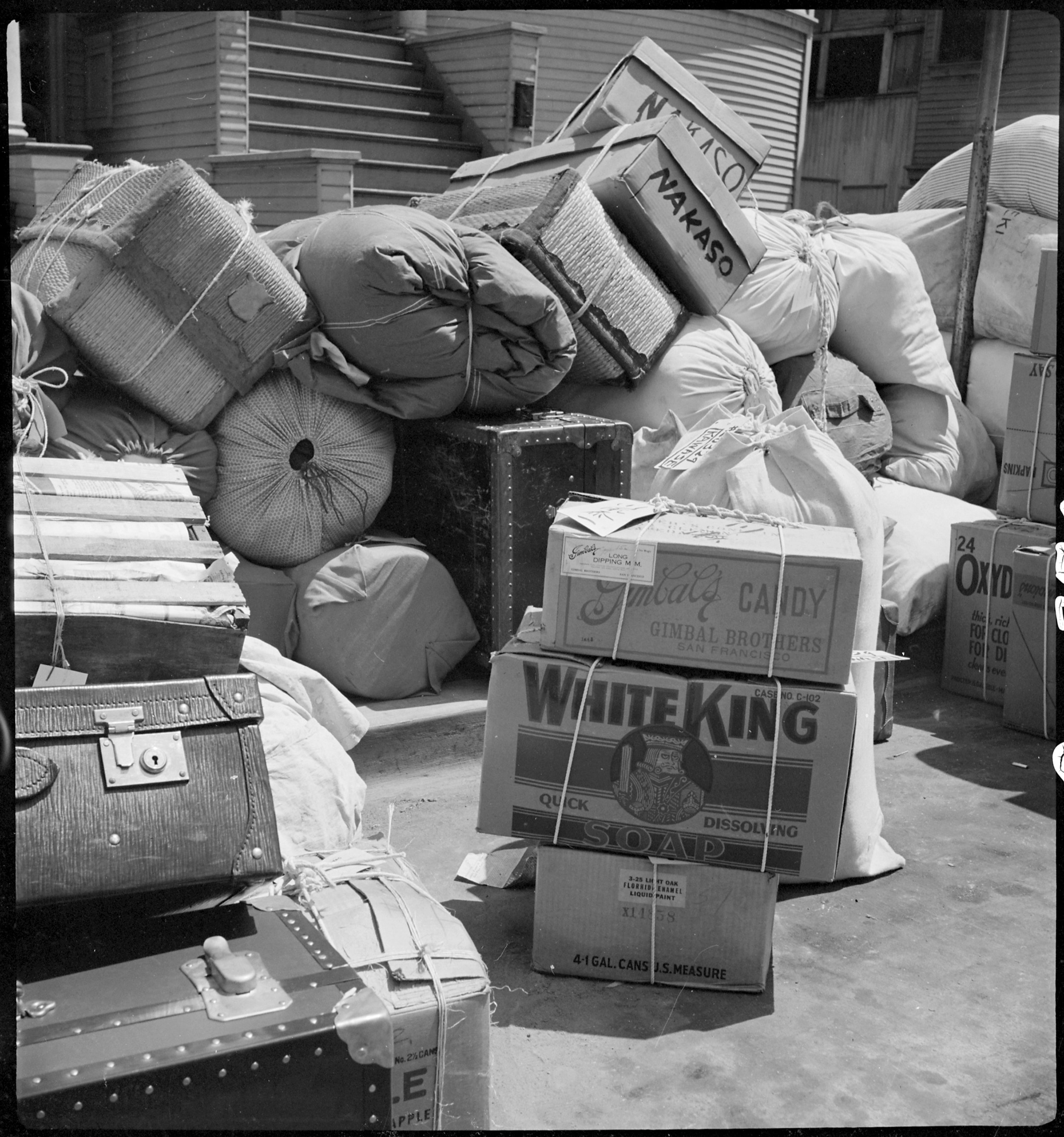

Below, I've selected some of Lange’s photos from the National Archives—including the captions she wrote—pairing them with quotes from people who were imprisoned in the camps, as quoted in the excellent book, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment.

I’ve also made a limited number of prints of her photos available for sale at Anchor Editions, and I’m donating 50% of the proceeds to two organizations fighting to protect immigrants: NILC and ACLU. Their fight seems especially important today given the current tide of anti-immigrant rhetoric, Muslim immigration bans, and the United States terminating DACA, which—if Congress does not pass the Dream Act—means 800,000 immigrants could lose their protected status.

This photo essay was originally published on December 7, 2016, the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. We’ve updated it this year, as the organizations we’re supporting continue to need your help. This month, print sale proceeds going to the NILC will be matched dollar-for-dollar by other NILC donors, so the NILC will get 100% of the value of any prints you order in December!

“A photographic record could protect against false allegations of mistreatment and violations of international law, but it carried the risk, of course, of documenting actual mistreatment.”

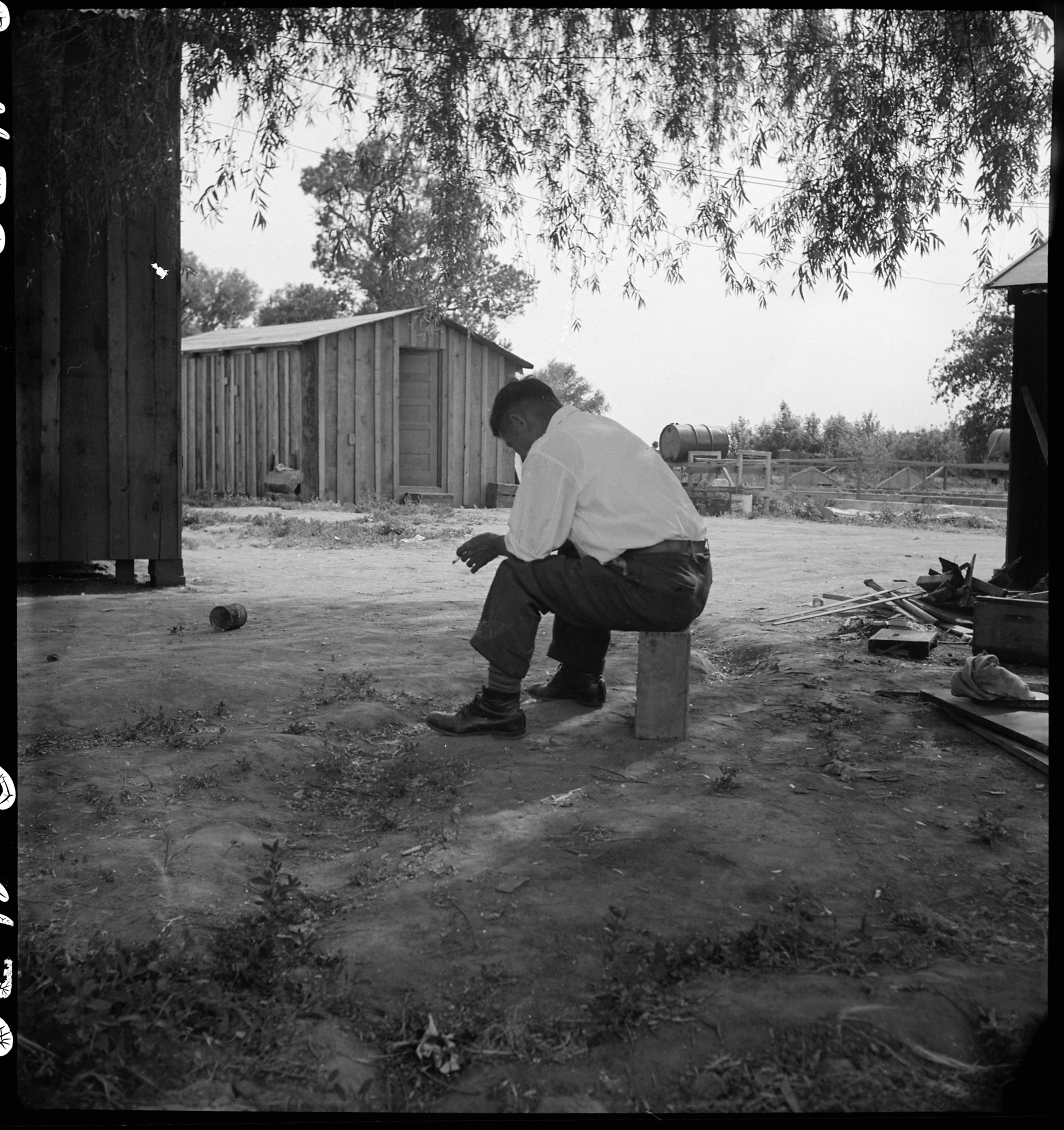

“We couldn’t do anything about the orders from the U.S. government. I just lived from day to day without any purpose. I felt empty.… I frittered away every day. I don’t remember anything much.… I just felt vacant.”

“We went down Pine Street down to Fillmore to the number 22 streetcar, and he took the 22 streetcar and went to the SP (Southern Pacific) and took the train to San Jose. And that was the last time I saw him.”

“As a result of the interview, my family name was reduced to No. 13660. I was given several tags bearing the family number, and was then dismissed…. Baggage was piled on the sidewalk the full length of the block. Greyhound buses were lined alongside the curb.”

“A Caucasian farmer representing a company was trying to get his workers to continue working in the asparagus fields until Saturday when they were scheduled to leave. The workers wanted to quit tonight in order to have time to get cleaned up, wash their clothes, etc.”

“The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil, possessed of American citizenship, have be come ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted.

…It, therefore, follows that along the vital Pacific Coast over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today. There are indications that these are organized and ready for concerted action at a favorable opportunity.

The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.”

“What arrangements and plans have been made relative to concentration camps in the Hawaiian Islands for dangerous or undesirable aliens or citizens in the event of national emergency?”

“Go ahead and do anything you think necessary… if it involves citizens, we will take care of them too. He [the President] says there will probably be some repercussions, but it has got to be dictated by military necessity, but as he puts it, ‘Be as reasonable as you can.’”

“It is said, and no doubt with considerable truth, that every Japanese in the United States who can read and write is a member of the Japanese intelligence system.”

“A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched—so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents—grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”

“We were herded onto the train just like cattle and swine. I do not recall much conversation between the Japanese.… I cannot speak for others, but I myself felt resigned to do whatever we were told. I think the Japanese left in a very quiet mood, for we were powerless. We had to do what the government ordered.”

“Although we were not informed of our destination, it was rumored that we were heading for Missoula, Montana. There were many leaders of the Japanese community aboard our train.… The view outside was blocked by shades on the windows, and we were watched constantly by sentries with bayoneted rifles who stood on either end of the coach. The door to the lavatory was kept open in order to prevent our escape or suicide.… There were fears that we were being taken to be executed.”

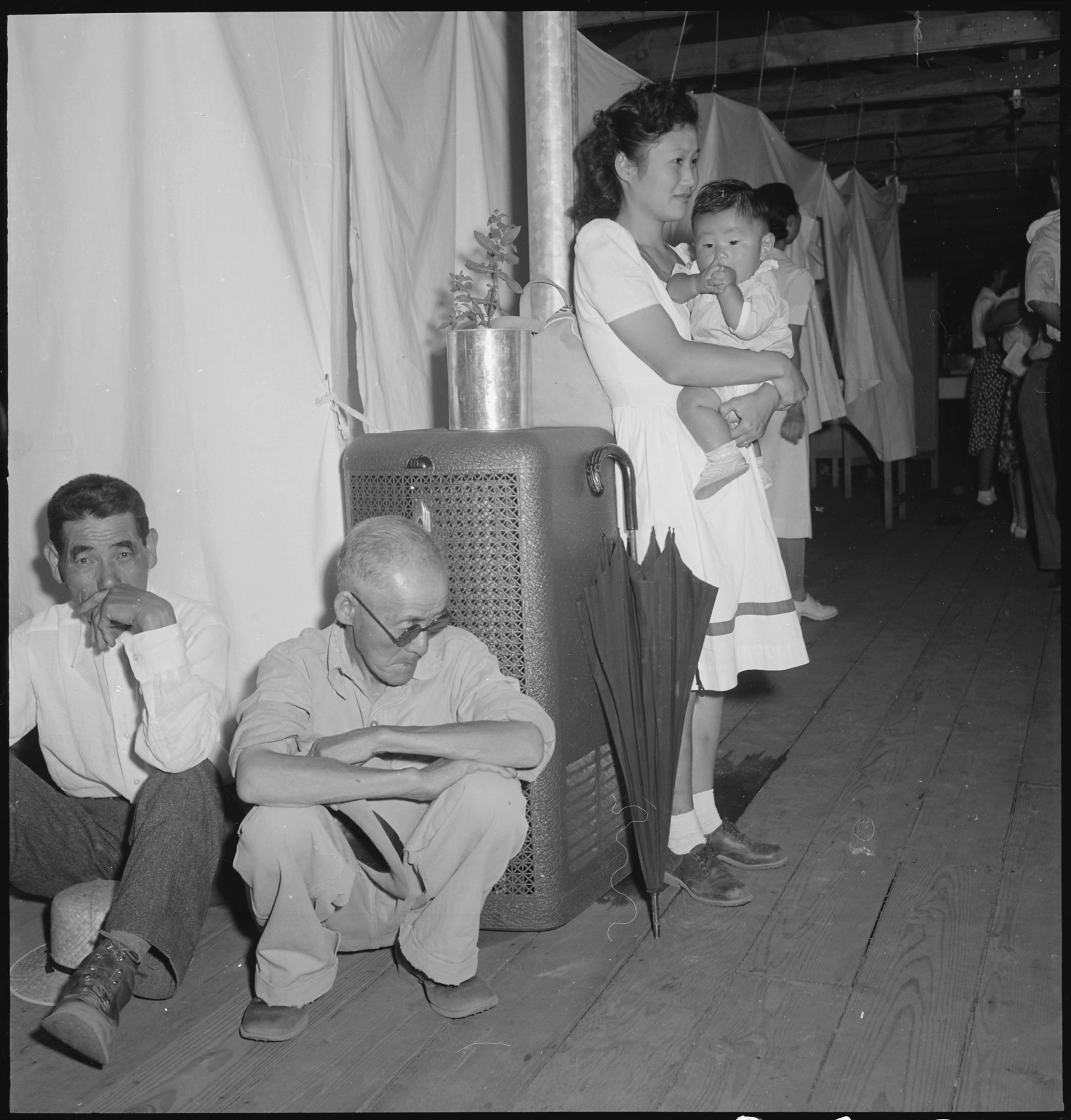

“We went to the stable, Tanforan Assembly Center. It was terrible. The Government moved the horses out and put us in. The stable stunk awfully. I felt miserable but I couldn’t do anything. It was like a prison, guards on duty all the time, and there was barbed wire all around us. We really worried about our future. I just gave up.”

“We walked in and dropped our things inside the entrance. The place was in semidarkness; light barely came through the dirty window on the other side of the entrance.… The rear room had housed the horse and the front room the fodder. Both rooms showed signs of a hurried whitewashing. Spider webs, horse hair, and hay had been whitewashed with the walls. Huge spikes and nails stuck out all over the walls. A two-inch layer of dust covered the floor.… We heard someone crying in the next stall.”

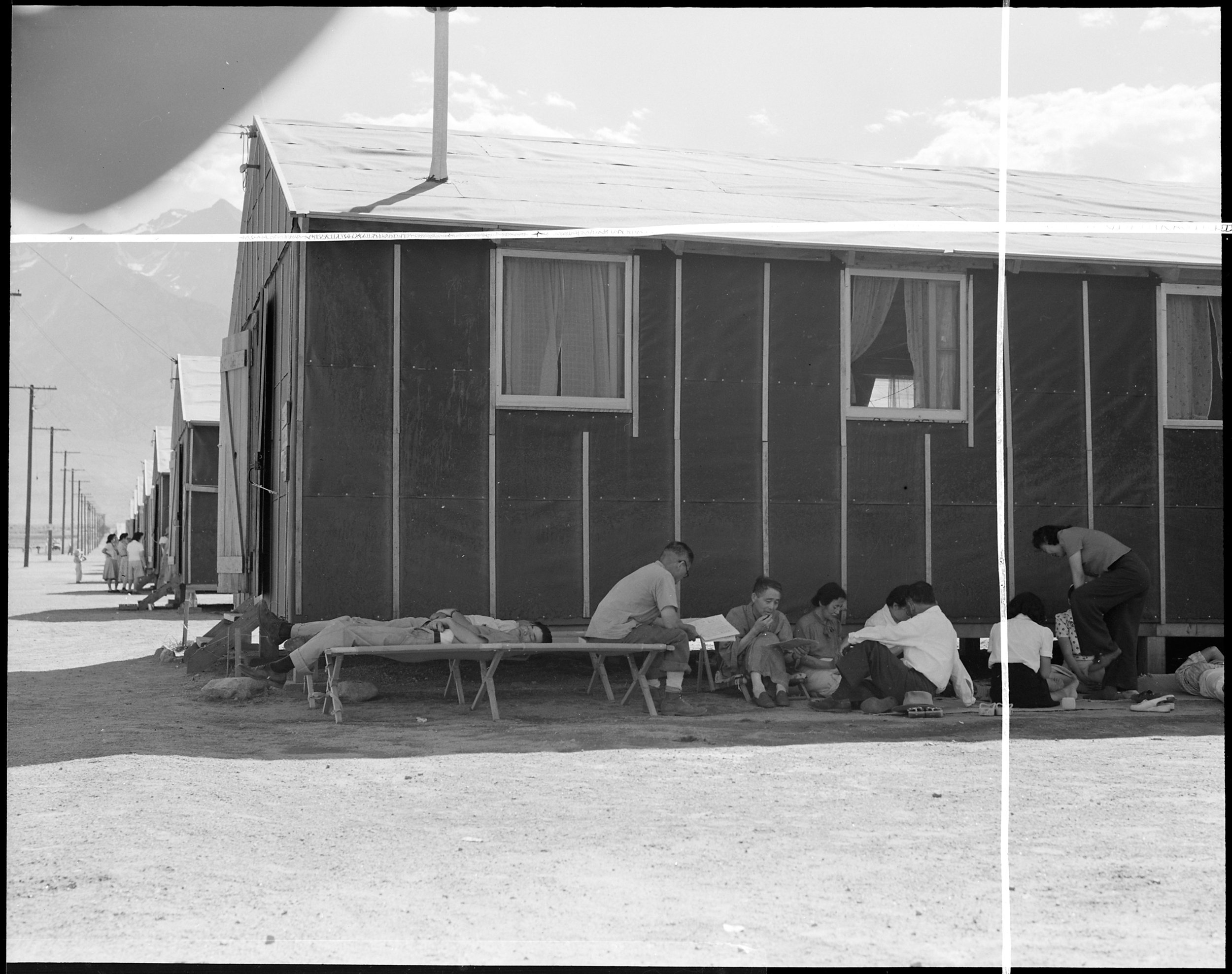

“When we got to Manzanar, it was getting dark and we were given numbers first. We went down to the mess hall, and I remember the first meal we were given in those tin plates and tin cups. It was canned wieners and canned spinach. It was all the food we had, and then after finishing that we were taken to our barracks.

It was dark and trenches were here and there. You’d fall in and get up and finally got to the barracks. The floors were boarded, but the were about a quarter to half inch apart, and the next morning you could see the ground below.

The next morning, the first morning in Manzanar, when I woke up and saw what Manzanar looked like, I just cried. And then I saw the mountain, the high Sierra Mountain, just like my native country’s mountain, and I just cried, that’s all.

I couldn’t think about anything.”

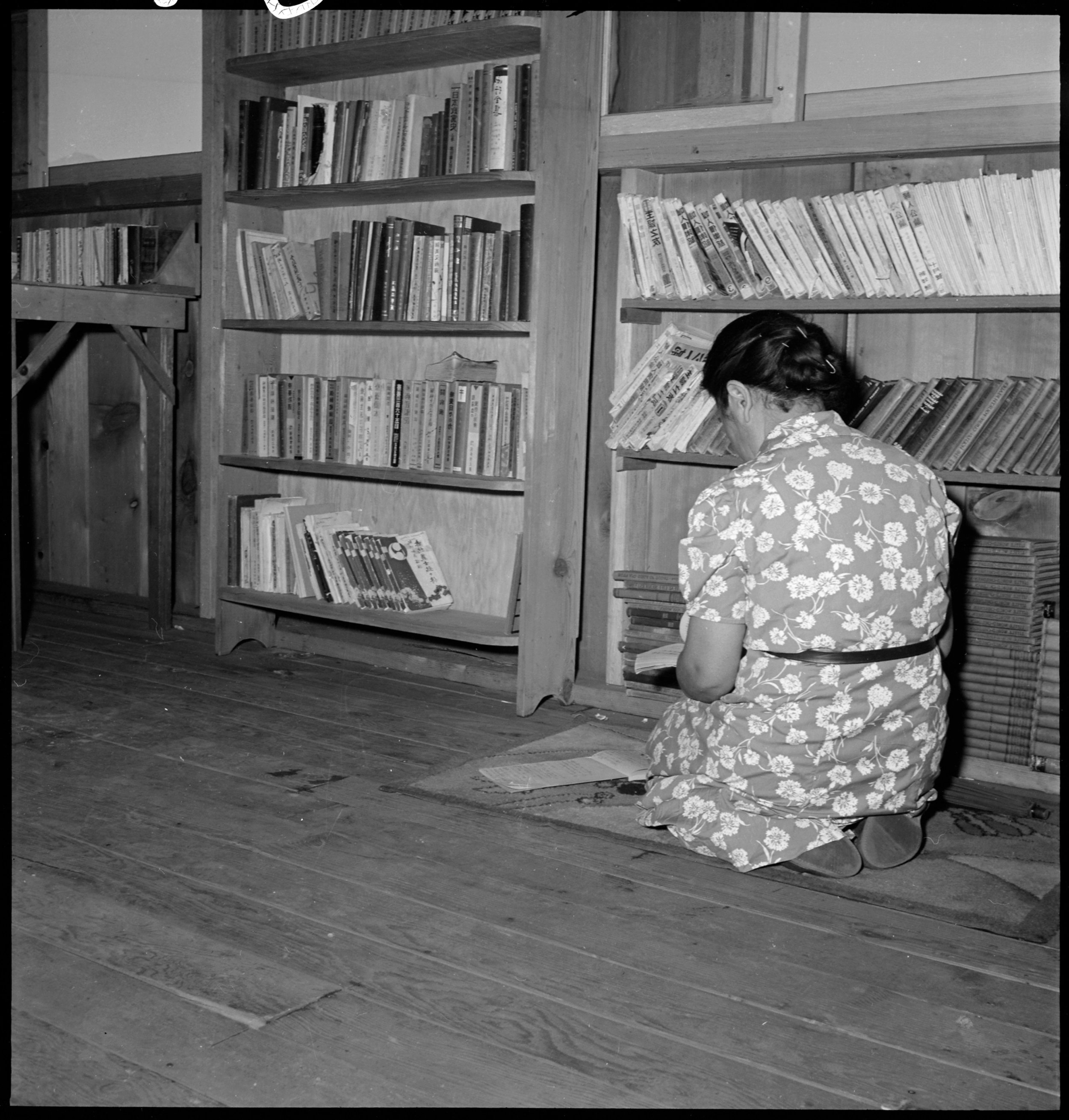

“Good manners eroded as meals were always hurried, reducing the ritual and elegance of Japanese cooking and serving to mere feeding the body. Maintaining personal cleanliness was difficult due to chronic shortage of soap and hot water. Lack of insulation and ventilation made the cubbyholes in which they lived freezing in winter and sweltering in summer. No decent provision for washing diapers. Dust. Mud. Ugliness. Terrible food—definitely not Japanese—doled onto plates from large garbage cans. Nothing to do. Lines for breakfast, lines for lunch, lines for supper, lines for mail, lines for the canteen, lines for laundry tubs, lines for toilets. The most common activity is waiting.”

“Each day rolled into weeks and weeks into months and months into years.”

Humor is the only thing that mellows life, shows life as the circus it is. After being uprooted, everything seemed ridiculous, insane, and stupid. There we were in an unfinished camp, with snow and cold. The evacuees helped sheetrock the walls for warmth and built the barbed wire fence to fence themselves in. We had to sing ‘God Bless America’ many times with a flag. Guards all around us with shot guns, you’re not going to walk out. I mean… what could you do? So many crazy things happened in the camp. So the joke and humor I saw in the camp was not in a joyful sense, but ridiculous and insane. It was dealing with people and situations.… I tried to make the best of it, just adapt and adjust.

— Mine Okubo, Tanforan Assembly Center

“It was a terribly hot place to live. It was so hot that when we put our hands on the beadstead, the paint would come off! To relieve the pressure of the heat, some people soaked sheets in water and hung them overhead.”

“Meanest dust storms… and not a blade of grass. And the springs are so cruel; when those people arrived there they couldn’t keep the tarpaper on the shacks.”

“They got to a point where they said, ‘Okay, we’re going to take you out.’ And it was obvious that he was going before a firing squad with MPs ready with rifles. He was asked if he wanted a cigarette; he said no.… You want a blindfold?… No. They said, ‘Stand up here,’ and they went as far as saying, ‘Ready, aim, fire,’ and pulling the trigger, but the rifles had no bullets. They just went click.”

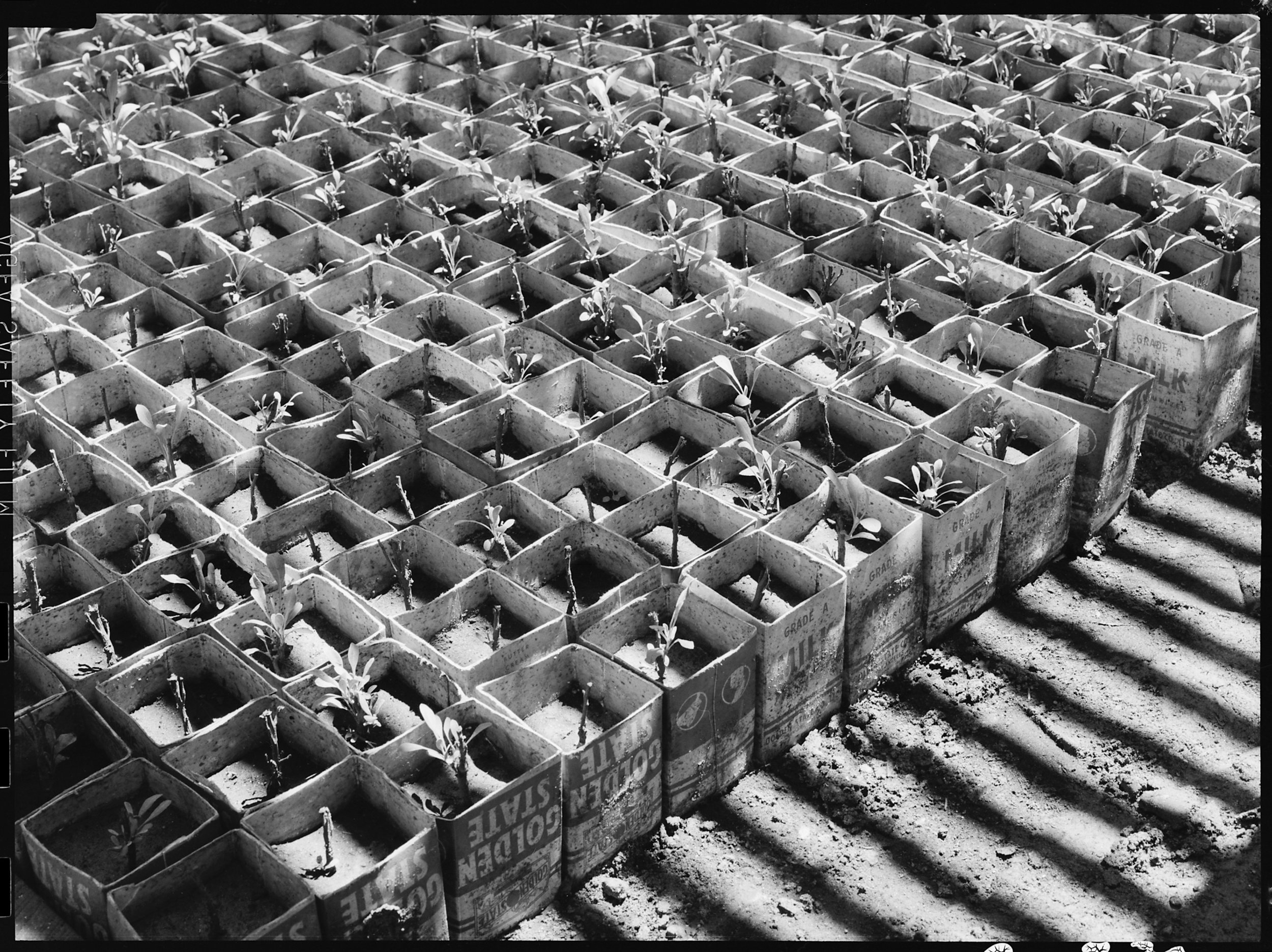

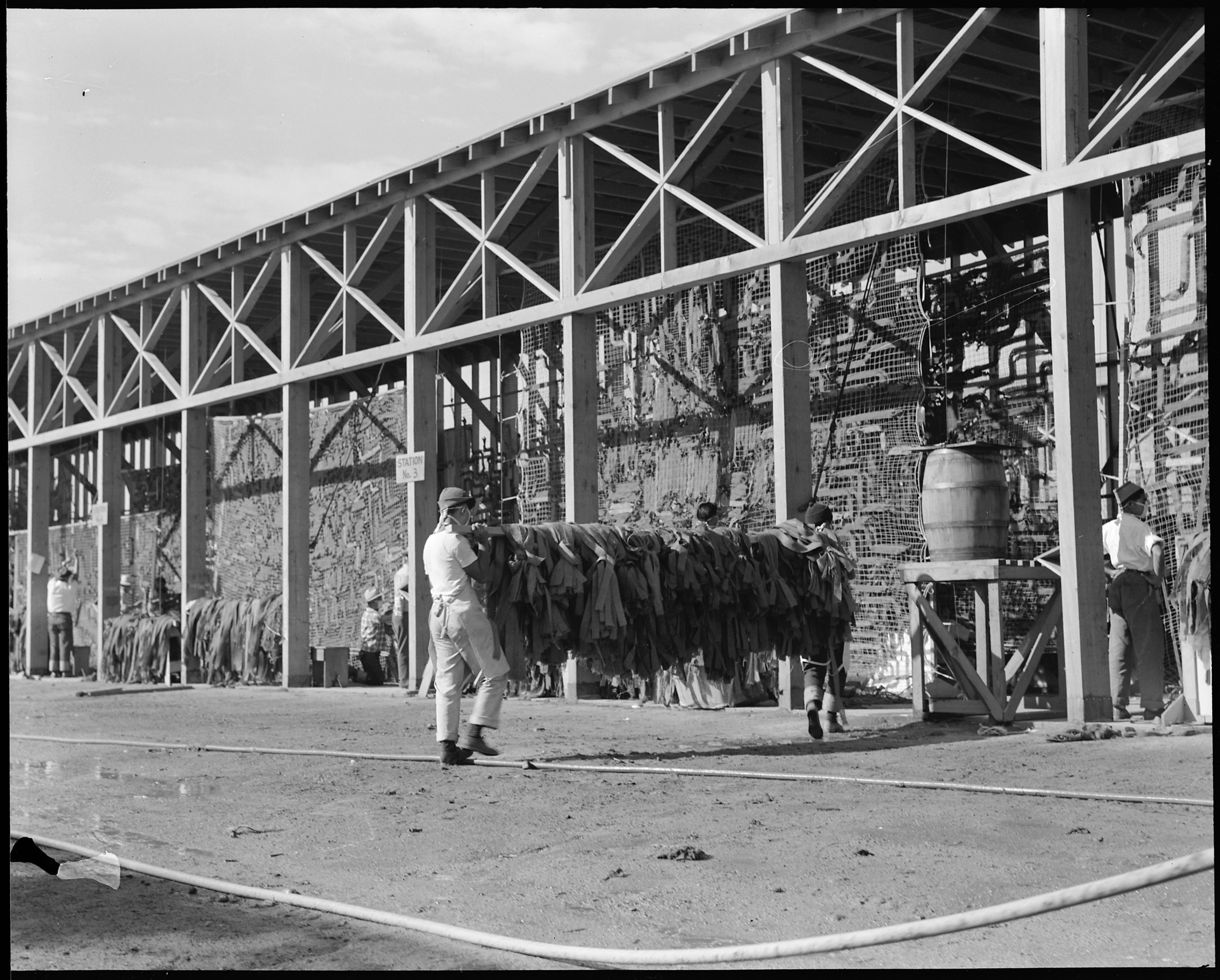

At Manzanar and at the Santa Anita Assembly Center near Los Angeles, army engineers supervised manufacture of camouflage nets. Huge weavings of hemp, designed to fit over tanks and other large pieces of war matériel, they were constructed from cords that hung from giant stands; the workers usually wore masks to protect themselves from the hemp dust. The army claimed that they were volunteers but they were in fact coerced by camp administrators, who were receiving requisitions for large numbers of nets from the army. (One of the first strikes at the camps occurred when 800 Santa Anita camouflage-net workers sat down and refused to continue, complaining of too little food. They won some concessions.) At Manzanar other internees worked in a large agricultural project to grow and improve a plant, guayule, that could become a substitute for rubber. With rudimentary and often homemade equipment, chemists and horticulturalists hybridized guayule shrubs to obtain a substance of tensile strength with low production costs. These undertakings were illegal under the Geneva Convention, which forbade using prisoners of war in forced labor, and as a result only American citizens were usually employed so that the army could claim that these were not POWs.

— Linda Gordon, Impounded

“One Jap became mildly insane and was placed in the Fort Sill Army Hospital. [He]… attempted an escape on May 13, 1942 at 7:30am. He climbed the first fence, ran down the runway between the fencing, one hundred feet and started to climb the second, when he was shot and killed by two shots, one entering the back of his head. The guard had given him several verbal warnings.”

“Without any hearings, without due process of law…, without any charges filed against us, without any evidence of wrongdoing on our part, one hundred and ten thousand innocent people were kicked out of their homes, literally uprooted from where they have lived for the greater part of their lives, and herded like dangerous criminals into concentration camps with barb wire fencing and military police guarding it.”

The government charged 63 members and seven leaders of The Fair Play Committee with draft evasion and conspiracy to violate the law. The trial judge, Blake Kennedy, addressing the defendants as “you Jap boys,” sentenced the members to three years imprisonment. The seven leaders were sentenced to four years in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

“I remember having to stay at the dirty horse stables at Santa Anita. I remember thinking, ‘Am I a human being? Why are we being treated like this?’ Santa Anita stunk like hell.… Sometimes I want to tell this government to go to hell. This government can never repay all the people who suffered. But, this should not be an excuse for token apologies. I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget.”

References

Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

John Armor and Peter Wright, Manzanar: Photographs by Ansel Adams, Commentary by John Hersey

Densho: Controlling the Historical Record: Photographs of the Japanese American Incarceration

Jonah Engel Bromwich, New York Times: Trump Camp’s Talk of Registry and Japanese Internment Raises Muslims’ Fears

Carl Takei, Los Angeles Times: The incarceration of Japanese Americans in World War II does not provide a legal cover for a Muslim registry

National Archives: Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority

![Sacramento, California. Harvey Akio Itano, 21, 1942 graduate from the University of California where he received his Bachelor of Science [in] Chemistry degree. He was chosen by the faculty as University Medalist for 1942 and was a member of Phi Beta](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5772d3bf414fb51b02df713d/1481063785870-BUEWYX7YTP963D13T8QR/537777.jpg)